The Phantom of the Opera: A Universal Super Jewel

Universal Pictures is the oldest surviving American movie studio, having been founded in 1912 in New York by Jewish German immigrant Carl Laemmle to compete with Thomas Edison’s company. Universal was the first motion picture corporation to give credits to cast and crew, laying the foundation for the “star system” to come.

In 1915, seeking to get away from Edison’s nuisance patent lawsuits, Laemmle purchased a 230-acre lot in Hollywood, California, and built Universal Studios, the largest film studio in America at the time. By 1916, a number of studios were operating in Hollywood, producing movies while also distributing them to theatre chains owned by the studios — Universal was unique in being a producer and a distributor, but not an exhibitor. Not owning a theatre chain, Laemmle sold Universal’s movies to independent theatres using a three-tier system:

Red Feather films were low-budget features, cheap programmers.

Bluebird films were more ambitious mainstream feature films.

Jewels were prestige productions with higher budgets and big stars.

Typically, Universal stuck to lower-budget fare that consistently made profits through reliable exploitation of popular genres such as westerns.

In 1919, 20-year-old motion picture producer Irving Thalberg, “the Boy Wonder,” was put in charge of Universal’s film output and began a move to increase the quality and prestige of the studio’s movies. Universal began creating one film a year called a “Super Jewel,” a big-budget affair from a top-name director with top stars, to be heavily promoted by the studio. 1922’s Foolish Wives, directed by Erich von Stroheim, was the first Hollywood picture to cost over a million dollars.

The 1923 Super-Jewel was The Hunchback of Notre Dame, based on the novel by Victor Hugo and directed by Wallace Worsley — a prestige historical costume drama with a budget of $1.25 million. Featuring massive reconstructions of the famous cathedral and Parisian streets, with a huge cast of extras, Hunchback exemplified the “more is more” strategy of the Super-Jewels. While Universal wished to emphasize the love story in the picture between Esmeralda, played by Patsy Ruth Miller, and Phoebus, played by Norman Kerry, quite frankly the focus of the public and press and the main reason the picture is remembered today was the central performance from actor Lon Chaney as the title character, Quasimodo.

Lon Chaney was born in 1883 in Colorado Springs. Both of Chaney’s parents were deaf, having met at a school for the deaf founded by Chaney’s maternal grandfather. He grew up fluent in American Sign Language and a master of pantomime. His stage career began in vaudeville in 1902, where he met his wife, who was a singer. The scandal of their divorce in 1913 forced Chaney out of theatre and into the film industry. He was initially on contract to Universal, but by the time he played Quasimodo he was an independent operator, having become so renowned for his skill as a silent film actor.

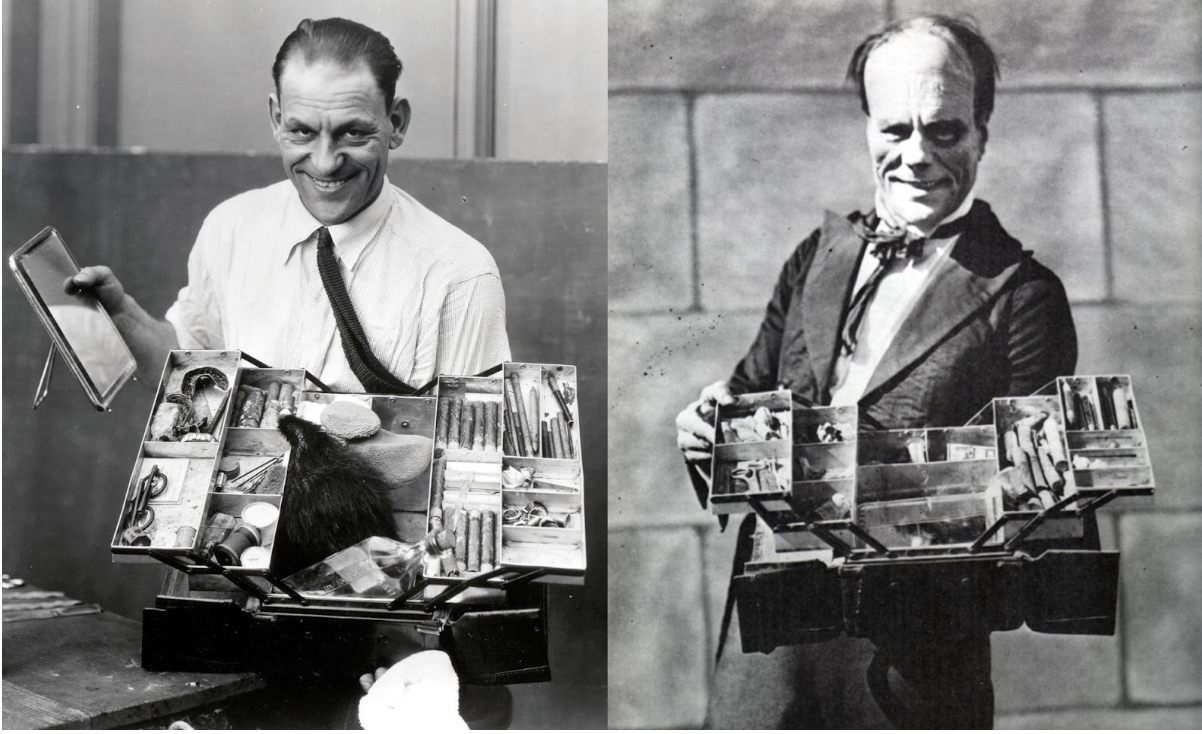

In those days, actors were responsible for their own make-up, as they had been for years on the stage. Chaney was a master of make-up and especially special effects make-up, using it to transform his physical appearance in each role. He was known as the Man of a Thousand Faces. A character actor at heart, Chaney was rarely presented as the romantic lead, but instead as a tortured misanthrope often with grudges against society, a victim of tragedy, pining for a girl he can never have. Despite often playing disfigured and frequently villainous characters, Chaney gave each role an inner pathos that elicited sympathy from the audience and made them love him and his characters, turning him into an unlikely and powerful star. Quasimodo was the ultimate expression of this archetype, and Chaney created a full-body make-up to transform himself into the tortured bell ringer, becoming in many ways the first Universal movie “monster,” though the film itself was not of the horror genre, which did not truly exist in America at that time.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame made $3.5 million, becoming Universal’s highest-grossing hit up to that point. That the story of Quasimodo became one which movies returned to again and again is almost solely due to the incredible performance from Chaney in the picture. And so, of course, Universal began hunting for a follow-up immediately.

The Super-Jewel for 1924 was Merry-Go-Round, a period romance initially directed by Universal’s top filmmaker, Erich von Stroheim. The romantic leads were played by Norman Kerry and a young ingénue named Mary Philbin. But Stroheim quickly fell behind schedule and went over budget, and his extravagances were no longer tolerated by Thalberg. When ordered to cut back on his ambitions, Stroheim attempted to go over Thalberg’s head and appeal to Laemmle himself, but this maneuver backfired and Stroheim found himself fired from the production.

Universal hired as Stroheim’s replacement Rupert Julien, an actor-turned-director from New Zealand who had found success with a 1918 World War I propaganda film where Julien had played a character much like von Stroheim. Julien’s aptitude as a director was limited, and he seemed to put much more effort into “playing the part” of a director, strutting around and ordering people like von Stroheim, but working from the plans left behind by the exiled German, Julien finished Merry-Go-Round and it was the 8th biggest hit at the box office that year. And so, Julien was picked to direct Universal’s Super-Jewel for 1925, the follow-up to the success of Hunchback, an adaptation of Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera.

There are two stories about how Universal ended up with the rights to Leroux’s novel. In one, Carl Laemmle was vacationing in Paris when he met Leroux and was given a copy of the novel, and upon recognizing it as a perfect starring vehicle for Lon Chaney, bought the rights. In the other, it was Chaney himself who bought the rights and negotiated with Universal to produce the film. In either case, the instinct was correct — if the aim was to ape the blockbuster success of Hunchback, Phantom seemed the ideal candidate: another period drama, centred around a Parisian landmark, based on a novel, involving a love triangle where one of the vertices was a misanthropic and deformed character for Chaney to embody. Norman Kerry and Mary Philbin would return from Merry-Go-Round as the romantic leads of Raoul de Chagny and Christine Daaé.

Universal spared no expense on Phantom’s production. Massive sets replicating key areas of the Palais Garnier were built — the grand staircase, the auditorium, the cellars, the roof, and the underground lake. No existing soundstage was large enough to hold them, so a new one was constructed — Stage 28, the first such stage constructed from concrete and steel rather than wood. Until it was demolished in 2014, it was the oldest standing stage in Hollywood. The Phantom sets were designed by Ben Carré, a French art director who had once worked as a designer and painter of backgrounds at the Paris Opera, and therefore had the familiarity with the Opera and its layout to direct the creation of the sets, which are one of the major highlights of the film. The sets were so huge that to get adequate wide shots of them the production had to leave the fourth wall off the entire soundstage building and shoot from outside the building itself, looking in.

Julien brought on his usual writer, Elliot J. Clawson, to pen the screenplay with an eye to a faithful adaptation of the novel. Clawson delivered, bringing the characters of Leroux’s novel to the screen, retaining its mystery structure and its understated ending. But from the beginning, there were misgivings about the film’s story from the studio. Universal wanted the focus on the opulent sets, the period setting, and the romance of Raoul and Christine. The studio was afraid of the script’s mystery and horror elements — mystery stories were risky at the box office, and the American film industry had never produced a horror that wasn’t also a comedy of some kind, where the villain is unmasked or the events revealed to be a dream.

As shooting began, problems began to show themselves almost immediately. Julien was in over his head, and it quickly became apparent to the crew and the cast. Cinematographer Charles Van Enger told a story where Julien requested that all the lights go out when the Opera’s chandelier was to crash. Van Enger knew the studio would flip if they spent all that money on the stunt only to not be able to see it, so he lied to Julien about the exposure and shot the sequence the way he had originally planned it.

Julien would shoot take after take with the young Mary Philbin, who was relatively inexperienced and naïve, using every excuse to get close to the actress and adjust her costume, her blocking, etc. Van Enger, Kerry, and Chaney all caught on to what Julien was doing harassing his lead actress and handled it in their own ways. Van Enger refused to shoot more takes, Kerry tried to run Julien over on horseback, and Chaney stopped speaking to Julien entirely and insisted on directing all the scenes he appeared in himself.

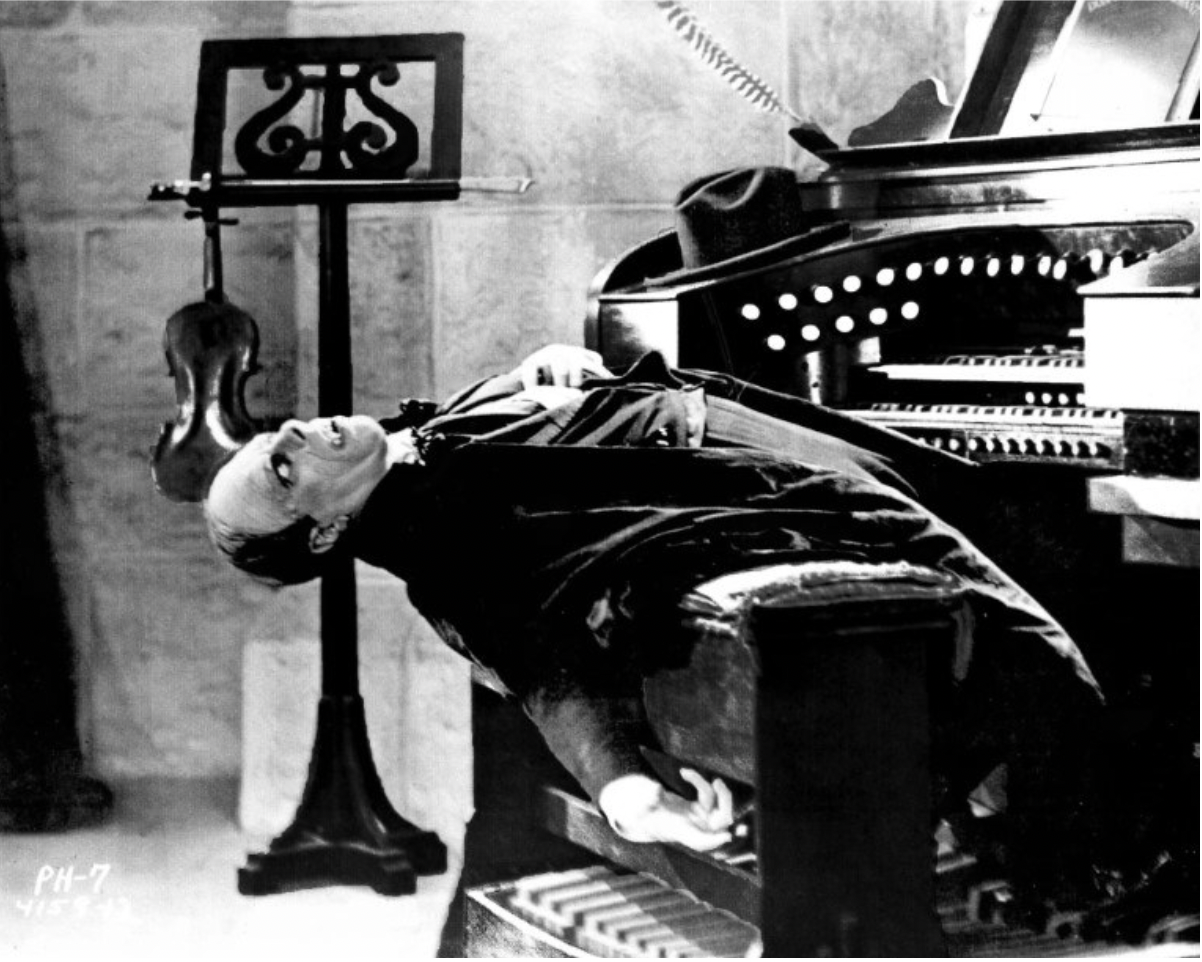

Chaney took Philbin under his wing and crafted the scenes in which he appeared as the Phantom with great care and attention. He told Philbin that the key to acting was to make the audience feel the emotion of the character — trying to feel the emotion yourself as the actor wasn’t important or necessary. Chaney was a very technical actor — a master of movement and gestures, and through the course of his career he became an expert in blocking, camera lenses, and lighting as well. He always ensured his scenes were lit so that his spectacular make-up would look its best.

Following Leroux’s description of Erik’s appearance as that of a living death’s head — with yellow skin stretched thin, beady eyes in dark sunken sockets, no lips, wisps of hair, etc. — Chaney created one of the most memorable screen characters ever seen. This was in the days before latex and foam rubber. He contoured the shape of his face with make-up, creating the illusion of sunken-in cheekbones and eyes. He stuffed wadding inside his cheeks to raise his cheekbones, wore a skullcap, embellished the wrinkles of his skin, and glued his ears to the sides of his head. He wore fake teeth which had small prongs that pulled his lips back. And using putty he altered the shape of his nose and used two small wires to pull his nostrils back to create the image of a flat skull-like nose. Application of dark and light paints on the face completed the illusion. To preserve the shocking reveal of Erik’s face in the picture, Chaney’s contract specified that no images of the make-up were to be used in the film’s promotional material or released in any fashion prior to the movie’s release. Universal, of course, picked up on this to great advantage in their publicity campaigns.

Chaney applied the same level of care to the creation of the Phantom’s mask, using a combination of a real mask with clever make-up to create the appearance of a porcelain half-mask with a veil of linen over the mouth. The make-up blended Chaney’s real eyes into the mask so that despite the illusion of painted eyes like a doll, Chaney could subtly change the mask’s expression from scene to scene to express the Phantom’s emotions.

Carl Laemmle’s plans for the film involved using every tool at his disposal to turn Phantom of the Opera into a visual spectacle that could not be missed, and that included the use of colour. After initially considering the Prismacolor process, Universal went with Technicolor, though this is not the famous “three-strip Technicolor” of the Golden Age of Hollywood. Instead, this was what is sometimes today called “two-tone Technicolor,” a subtractive colour process where a special camera was fitted with a beam splitter so that the light that entered the lens would hit two frames of the film strip simultaneously (one upside down relative to the other). The beam splitter was fitted with special filters that would filter the light into the parts of the spectrum containing red and green, respectively. The two black-and-white frames would then later be dyed — the green-filtered frame dyed red and the red-filtered frame dyed green — and the two frames would be glued together to overlay them and create the illusion of colour through differing values of red and green. The process meant that film had to be run through the camera at twice the regular speed to expose the right amount of frames, creating a slower frame rate for Technicolor when projected back. It also required twice as much light be used, or else the two frames would appear too dark. Until Phantom, the process had only been used for shooting in exteriors in daylight, where there was ample natural light. Phantom used the process on the sets, for the opera scenes and for the spectacular Bal Masque sequence. These Technicolor scenes were thought lost until the Bal Masque was famously recovered by David Shepard in the 1970s. Very recently, a Technicolor print for the film’s opening ballet scene was recovered in Europe and has been integrated into a full restoration of the picture for the first time for Calgary Cinematheque’s presentation.

Other tricks were also utilized — in a key scene on the roof of the Opera, a special colour process called the Handschiegl process was used to render the Phantom in colour while the rest of the frame was monochrome. This process required creating a stencil-like matte for each frame of the film to separate Chaney’s figure from the rest of the image, so that he could be coloured frame-by-frame using special dyes. The majority of the film meanwhile was tinted various colours, as was the custom in silent movies of the era to indicate lighting, setting, time of day, and mood.

When all was said and done, with $500,000 spent on a 10-week shoot, Rupert Julien brought in 350,000 feet of footage which was cut by film editor Gilmore Walker into a 10-reel picture — 1,000 feet per reel, at 14 minutes per reel for projection speed. 2 hours and 20 minutes for Rupert Julien’s cut of The Phantom of the Opera.

After months of rather sensational hype around the picture from Universal’s publicity department, Carl Laemmle thought it wise to bring the film to Los Angeles to be screened in previews to discover what audiences thought of it. On January 7th and January 26th, 1925, Rupert Julien’s director’s cut of Phantom of the Opera played at Sid Grauman’s theatre. Faithful to Gaston Leroux’s novel, it featured all the primary characters and included aspects of the story the studio had been very nervous about — such as a nighttime visit by Christine to her father’s grave in rural France where the Phantom appeared to hurl skulls at Raoul, and Leroux’s ending where the villain has a change of heart and decides to let Raoul and Christine live after she kisses him, before dying of a broken heart. In Julien’s version, the picture ended with an angry mob formed by the opera’s workers who had been so terrorized by the Phantom finding the madman’s body dead at his organ.

Julien’s version, and the attempt at a completely faithful adaptation of Leroux, died there as well. The preview screening was a disaster, as audiences complained about “too much horror, not enough romance,” and comments requesting less mystery and melodrama and to “put some gags in to relieve the tension.” In short order, Julien was fired, the picture was pulled from the release schedule, and Universal had to decide what to do to save the “Super-Jewel of 1925.” But that is a story for next time.

Written by Ben Rowe.