The Many Versions of Phantom of the Opera

We often hear stories today about films taken away from their directors and re-edited by studios against their wishes, stories which often lead to a special “director’s cut” release down the line. We also see many movies altered by their original creators over time as well, creating a preponderance of alternate versions to sift through when sitting down and choosing to view one of our favourite films.

But this state of affairs is not a recent development in the history of cinema. Test screenings and studio interference have been part of the business for a long time, and alternate versions have existed for a variety of reasons going back to the days when different territories had different censorship requirements, causing a proliferation of edits even within just the United States.

Rupert Julian had delivered his version of Phantom of the Opera to Universal after a 10 week shoot and $500,000 spent. His editor, Gilmore Walker, had delivered a 10-reel picture, about 2 hours and 20 minutes long. It was predominantly faithful to the Gaston Leroux novel, and Universal - concerned about their investment - screened it in two previews in Los Angeles on January 7th and 29th in 1925.

The test screenings were a disaster. Audience response was resoundingly negative. Viewers were alarmed at the picture’s dark horror qualities, as Universal had been promoting Phantom largely as a costume romance with a mystery element. A summary of the comments read: “There’s too much spook melodrama. Put in some gags to relieve the tension.” Audiences disliked the amount of horror, and they disliked the ending, where Christine’s kiss causes the villain to redeem himself and let her and Raoul go, and the angry mob upon reaching his lair discovers that he has died of a broken heart. “Better to have kept him a devil to the end,” read the comments, despite the fact that the Phantom’s redemption is very much the point of Leroux’s original story. Another element that audiences found confusing was the character of the Persian, a daroga from Mazanderan who had tracked the Phantom across Europe and knew his secrets. Introduced early in the picture as a red herring for the identity of the Phantom, audiences did not understand if he was meant to be a hero or a villain - Leroux’s character was a hero, but a non-white hero was a difficult sell to 1920s white America.

Rupert Julian was fired, and in his place was hired Ernest Sedgwick to do extensive reshoots and “save” the picture. Sedgwick was a veteran of Universal’s westerns - cheap B-movies designed as filler for independent theatres, they were easy crowd-pleasing moneymakers. Raymond Schrock became the new producer, Virgil Miller brought in to shoot the new version, and Edward Curtis was the new editor.

Sedgwick’s edit cut out the scarier scenes from the preview version, as well as reducing the screentime of several ancillary characters: the prima ballerina La Sorelli, the dancer Meg Giry, her mother Madame Giry, and the scene shifter Joseph Buquet all had their parts drastically reduced. Buquet’s murder scene was cut - his body is still found, but we do not see the Phantom kill him. The entire subplot of the Phantom playing the violin and pretending to be the ghost of Christine’s dead father was excised. The visit to Christine’s father’s grave at Perros at night, where the Phantom rolled skulls at Raoul, was considered too scary and was cut, and so was Christine’s surrogate mother, Madame Valerius. Scene order was re-arranged, and Sedgwick filmed a vast amount of new material to replace all the cut footage.

In Sedgwick’s version, there is an entirely new subplot set outside the Opera where Raoul’s love for Christine had a new rival - the Russian Count Ruboff. Sedgwick felt that the Phantom couldn’t possibly be a real contender for Christine’s love, being a monster, so for there to be an audience-pleasing love triangle, Raoul needed a “real” rival. This subplot included a duel between Raoul and Ruboff, a big bar fight, attacks by bandits on the road, and a new comedic addition in Raoul’s servant Chicot - a slapstick bumbler who tries to woo Christine’s maid. Sedgwick also shot new scenes revealing that the Persian was not in fact ethnic after all - but merely a French policeman masquerading as a foreigner as part of his plan to get close to the Phantom and arrest him!

Finally, Sedgwick shot a new ending for the picture, where upon the arrival of an angry mob at the Phantom’s lair, the villain takes Christine hostage, steals a carriage, and is pursued through the Paris streets in a rousing chase sequence - economically reusing the Paris street sets and cathedral facade from The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The mob catches up to the Phantom, and kills him.

Sedgwick’s version ran 11 reels, two hours and 34 minutes, longer than Julian’s but containing the elements the studio asked for: romance, comedy, action, and less horror and mystery! By the time he was done, costs on the picture had risen above $600,000. Universal arranged for a new preview screening, on April 26, 1925.Reaction was even more negative than to Julian’s version. The picture was booed off screen. The summary of the audience comments: “The story drags to the point of naseum.”

Universal was really in trouble now, having invested so much in a picture that seemed unable to please audiences. Raymond Schrock and Ernest Sedgwick were removed from the production, and Carl Laemmle did perhaps the smartest thing he could have done - he gave control of the picture to Lois Weber, one of Universal’s top directors for the previous ten years, well known for her excellent sense of cinematic narrative and storytelling. Weber was the first American woman to direct a feature-length film, and was known for creating commercially successful films that still carried humanist messages concerned with social justice.

After all the money Universal had spent on the film, Weber was not given any ability to produce more reshoots. So she and her editor, Maurice Pivar, instead set to work looking at all the footage shot so far and assembling it into a coherent story that would sweep audiences along with its story.

Weber restored the original shape of the story from Rupert Julian’s version, doing away with much of Sedgwick’s extra side plots. She did, however, simplify the narrative by removing several ancillary characters and sequences - the Perros graveyard, Madame Valerius, and Buquet’s murder stayed out, but Sedgwick’s additions of Count Ruboff and Chicot also hit the cutting room floor. What remained from Sedgwick was the new identity of the Persian as Ledoux of the Secret Police, and the action finale with the mob chasing the Phantom through Paris.

The result was a stripped down version of the original story that focused on using the mystery and romance in the early scenes to draw the audience into the story, so that the horror elements could emerge at the midpoint without overwhelming viewers. Weber and Pivar got the running time down to nine reels, with a running time of 1 hour and 45 minutes. This is the version that finally officially premiered in New York at the Astor Theatre on September 6, 1925.

Finally, Universal had what they were looking for. While critics still complained about the amount of unpleasant horror in the film, it turned out that Weber had cracked the code for getting audiences on board. People fainted in the theatre when the Phantom’s face was revealed, and the Astor Theatre shows had lines around the block. Confident in the product at last, Universal put Phantom into general release across the United States on November 15, 1926. The picture ended up making $2 million at the box office, justifying all the money spent on it much to Carl Laemmle’s relief. In Phantom of the Opera, Lon Chaney had created the first Universal horror monster.

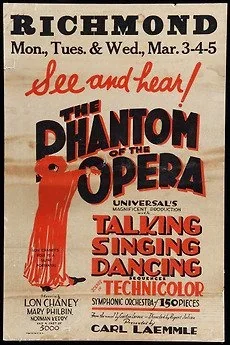

In those days, before television, home video, or streaming, the long tail of income from a film would come from occasional re-releases into theatres. By 1929, Universal was looking to re-release Phantom, but faced a problem – the new technology of sound had taken America by storm and silents were rapidly becoming unsellable. To combat this, a plan was undertaken to add sound to Phantom. The original cast would be brought in to record dialogue over the original scenes, and a music and sound effects track would be added. There was a catch, however - Lon Chaney was now under contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, who would not loan him to Universal for the dubbing, and Chaney’s contract also specified that no one else was allowed to dub his voice. So even in this sound re-release, the Phantom’s scenes would remain silent.

Once again, the film would be re-edited and scenes would be reshot. Mary Philbin and Norman Kerry both returned to shoot new scenes in sound, and all of the scenes of singing on the opera stage were reshot so actual singing could be recorded. To this end, the actress who originally played Carlotta, Virginia Pearson, was replaced by opera singer Mary Fabian, and Pearson’s role in other scenes was changed to being Carlotta’s mother through the use of rewritten title cards and dialogue. To make room for the new scenes, old ones were cut out and the story was once again simplified, with the entire first act being re-arranged. The new scenes were directed this time by Ernst Laemmle, the boss’s nephew, and edited by Frank McCormick, with the new score by Joseph Cherniavsky.

This version ran one hour and thirty minutes, and perhaps 40% of the footage is functionally identical to the old 1925 version. It is not precisely the same because even for the scenes that remained silent, the new print was struck from a camera B negative. During this era, films would have a primary negative and then a back-up negative shot from a camera right beside the primary camera, as prints in those days were struck directly from the negative. This would damage the negative over time, and so the back-up was used for archiving. By using the back-up negative to provide the scenes in the 1929 re-release, it ensured that today no negative for Phantom of the Opera survives.

Universal used the “sound on disc” system at that time, where films were projected in the theatre while a record was played in sync over the sound system. The new scenes had been shot at the “sound speed” of 24 frames per second, while the original silent scenes had been shot at 20 frames per second, so when the sound version was projected at 24 frames per second the older material would appear to run slightly too fast.

This elaborate new version was released on December 15, 1929 and made another million dollars for Universal, though ultimately audiences were confused by the hybrid approach and critics felt the re-release was something of a cheap cash grab, which it was. Due to the way it was produced, this alternate sound version has not fully survived to the modern day, though part of its legacy certainly has.

1929 was still in the early days of sound, and it had not been evenly adopted worldwide. Additionally, even for foreign cinemas equipped for sound it was easier to swap out title cards than dub dialogue. For this reason, a silent version of the 1929 re-edit was created, with only the music and sound effects track from the sound version optionally attached, and title cards used throughout even while retaining some of the re-shot footage and the shorter running time and simplified scene order.

Today, no negative material survives for Phantom of the Opera, and we have no surviving prints of the Los Angeles or San Francisco preview versions. The 1925 General Release version that established the film’s fame has not survived in 35mm, only in heavily damaged 16mm prints that Universal used to send out for home rentals. Instead, the only high quality 35mm print of Phantom that has survived is the silent version of the 1929 sound re-release.

For this reason, it is this version that has formed the basis for all modern restorations and releases on television, home video, and repertory screenings throughout the years. The quality of the 35mm print, property of the archive at George Eastman House, is quite high as it was created for archival purposes in 1948. For this reason restoration efforts have focused on this high quality source, and the original 1925 General Release version of Phantom of the Opera has fallen quietly out of common memory.

For Calgary Cinematheque’s 100th anniversary screening at the National Music Centre, I have created a special reconstruction of Lois Weber’s 1925 General Release version of Phantom of the Opera. This was done by using the high quality 35mm print for those scenes found in both 1925 and 1929, edited to match the surviving 16mm print of the 1925 version. For those scenes which were cut from the 1929 version, the 16mm material has been used to patch the holes. The Technicolor footage of the Bal Masque recovered from the company’s archive in 1971 has been used in this reconstruction alongside a newly discovered sequence of the opening ballet in Technicolor discovered in a European archive and placed within a restoration of the film for the first time. The Handschiegl colour process scene is also present in this reconstruction, while tint colours have been restored by referencing what colours are indicated for each scene in Elliot J. Clawson’s original screenplay and by referencing a 1927 Eastman Kodak tinting manual.

In this way, we hope to transport audiences back 100 years to 1925 and enjoy the version of Phantom of the Opera created by the great Lois Weber, which so entertained audiences when it was first shown across the United States.

Written by Ben Rowe.