Gaston Leroux and The Original Novel

First edition cover

The Phantom of the Opera is one of those stories that, like Frankenstein, Dracula, or Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, has evolved so much over the course of its myriad adaptations that returning to the original source material can occasionally be a shock. For one, while the novel touches on genres like romance, horror, tragedy, and historical fiction, a modern reader might be surprised to find that for the most part the original novel is structured as a mystery. This would not have been a surprise, however, to any French readers in 1910 when the novel was originally published, as its author, Gaston Leroux, was already one of the most acclaimed writers of mystery fiction in the world.

Gaston Leroux

Gaston Leroux was born May 6, 1868 in Paris, to an old wealthy noble family with prominent political connections. He had studied to become a lawyer, but upon the death of his father he inherited over a million francs, but as an eighteen year old university student he ended up blowing through it on a lavish lifestyle until he was bereft of funds a year later. He did not wish to become a lawyer, and had discovered a love of writing, and so became a journalist, working as both theatre critic and court reporter for L’Echo de Paris. His work won the attention of editors at Le Matin, and he began covering trials for that prestigious newspaper including becoming the first French journalist to interview accused persons in jail awaiting trial. He was promoted to foreign correspondent, covering the 1905 Russian Revolution.

However, after the grueling work load of being an international journalist, Leroux wished to pursue a more relaxed writing career, and quit his position to become a novelist. His great inspirations were Edgar Allen Poe and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and in 1907 his novel The Mystery of the Yellow Room began serialization, being released as a single volume the following year. Starring the fictional reporter Joseph Rouletabille, the novel is a classic locked room mystery and indeed among fans of mystery novels it is considered the example par excellence of the locked room sub-genre. The book was immensely successful, and has been adapted to film seven times, starting in 1913 and with the latest in 2003. It began a series of seven Rouletabille books which ran until 1922.

The Phantom of the Opera marked a shift for Leroux from the Rouletabille mysteries, to be sure, but in its structure it still followed the conventions of a mystery, while also allowing Leroux to draw upon his history as a journalist and his knowledge of both the Opera House from his time as a theatre critic and his knowledge of the gossips and scandals of the Parisian elite. He drew inspiration from other stories like Trilby and Beauty and the Beast, but also from longstanding rumours about the Opera House and the people involved in it.

The novel begins with a famous prologue which declares “Le Fantôme de l’Opéra a existé,” the Phantom of the Opera did exist, and then launches into an explanation of how Leroux as a reporter interviewed all the surviving people involved with the case and pieced together the narrative from their testimonies. The novel is therefore presented to its readers as an historical account revealing the true story behind several curious and unexplained incidents in the Opera’s history. With Leroux setting his tale some thirty years earlier and using inspiration from incidents ranging from twenty to fifty years earlier, he could thereby draw on the vague memories of his readers by piecing together enough true details with enough half-remembered ones to create a convincing illusion of reality to his story.

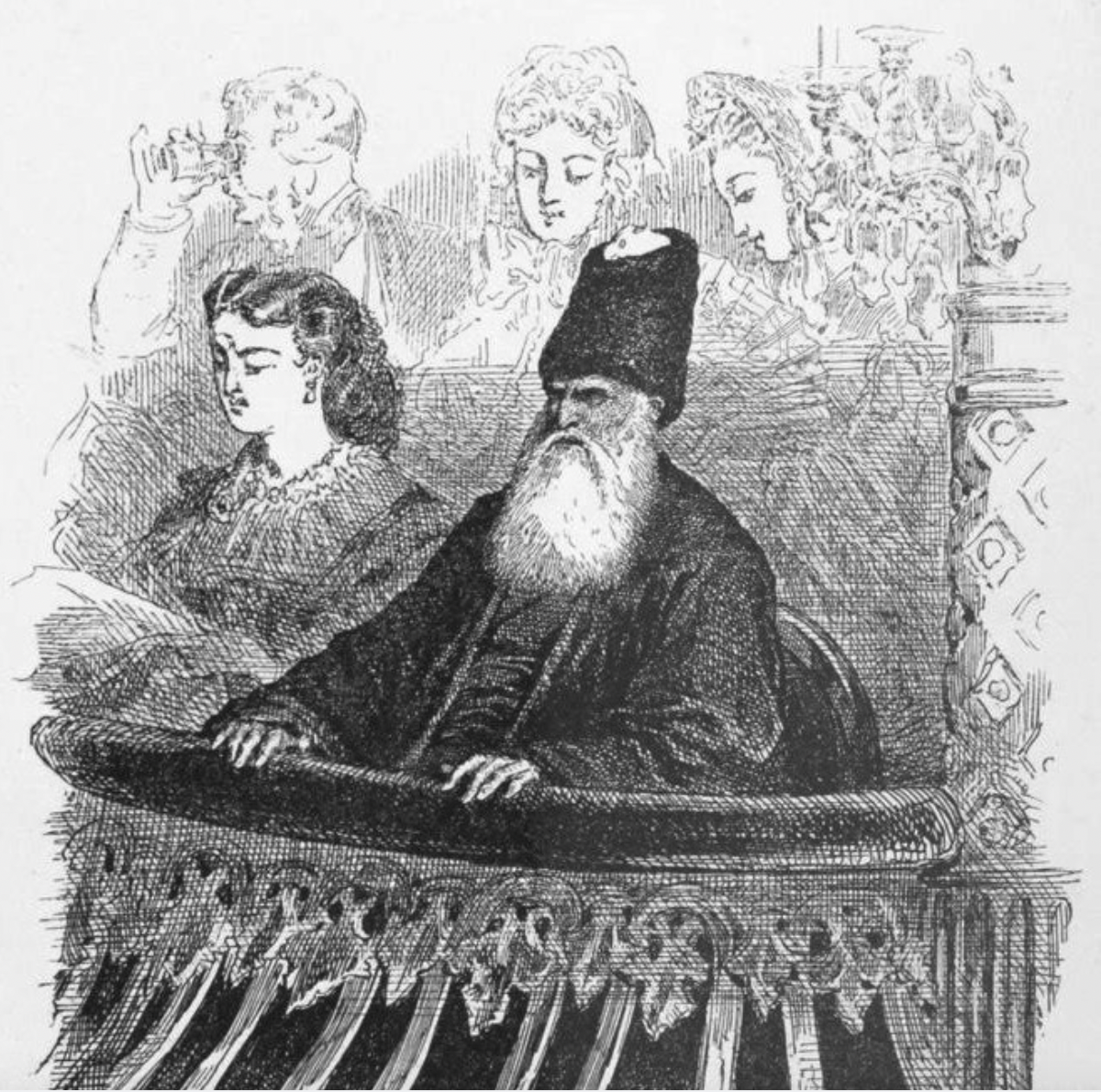

Illustration by André Castaigne from the original novel

The story was originally serialized beginning in 1909, before being published in a completed volume in 1910. The opening of the novel presents the Paris Opera as a buzzing bee hive of interconnected people, with the Opera Ghost a persistent rumour in the background. But is he truly a supernatural ghost, or is he really one of the characters we are introduced to, enacting some kind of secret agenda? We meet a dizzying array of characters: Phillipe, Comte de Chagny; his younger brother Raoul; Raoul’s childhood sweetheart Christine Daaé, Christine’s friend Meg Giry, Meg’s mother Madame Giry, Christine’s surrogate mother Madame Valerius, opera prima donna Carlotta, star ballerina La Sorelli, new managers Moncharmin and Richard, scene changer Joseph Buquet, and the ever mysterious “Persian” who stalks about the place.

Eventually, the tone shifts when the Phantom drops the opera’s chandelier on the audience and steals away with Christine, and slowly the love triangle we know between Raoul, Erik (the Phantom), and Christina emerges. Christine is taken down to the Phantom’s lair on the lake five levels below ground and removes his mask to discover that he has lived with an horrific disfigurement since birth. She returns to the Opera and meets Raoul at the Bal Masque, describing her experiences. Raoul sets a trap to catch the Phantom and ends up teaming up with the revealed-to-be-heroic Persian who knew Erik when he created death traps for the Shah, and the two of them end up in a torture chamber as Erik holds their lives over Christine’s head. It’s all extremely melodramatic, but it ends on a small, sad note of emotion: Christine kisses Erik, and upon receiving the first act of physical affection ever in his life, he agrees to let Christine and Raoul go, and later passes away of a broken heart.

The story of the Phantom himself was drawn from multiple sources: rumours of an Opera Ghost, tales of skeletons found deep in the cellars, but it also worth remembering the story of Joseph Merrick, the so-called Elephant Man, who achieved some fame in the 1880s for his extreme congenital deformities, and who wept when shown kindness by the nurses of the London Hospital. The incident of the falling chandelier was taken from the real life occurrence in 1896 of a counterweight from the chandelier crashing down upon the audience, killing one person and injuring seven others.

The opera performed in the novel is Gounod’s Faust, the story of an old man who makes a deal with a devil named Mephistopheles to be young and handsome so he can win the hand of a girl named Marguerite. The prima donna role in the opera is Marguerite, and in the story the characters of the Swedish ingenue Christine Daaé and established prima donna Carlotta vie for the part. Leroux based many of the characters in his novel on real figures, and in this he took inspiration from Swedish singer Christina Nilsson’s feud with French singer Marie Caroline Miolan-Carvalho, and her rivalry with the Spanish soprano Adelina Patti, who was perhaps the most famous singer in Europe at the time.

Christina Nilsson

Carvalho as Marguerite

Christina Nilsson was born to a poor family in rural Sweden in 1843, and like Christine Daaé she was discovered and trained by a Madame Valerius, in reality the Baroness Leuhusen. She studied in Sweden and in Paris, and performed at the Thèâtre Lyrique from 1864 to when she joined the Paris Opera in 1868. She was the first to perform the role of Ophelia in Ambrose Thomas’s operatic version of Hamlet, and she controversially took over the role of Marguerite in Faust in 1869, a part which was normally played by Caroline Carvalho, who had originated the role. This led to a battle between the theatre critics of the day over the two singers, which had a nationalistic tinge due to Carvalho’s heritage. Eventually Nilsson would move on to perform at other operas all over the world, and Carvalho would resume her position of prima donna of Paris. Nilsson’s first marriage, to the French stockbroker Auguste Rouzard, ended in disaster when he mismanaged all her money and died of illness. In 1887, Nilsson wed the Count de Casa Miranda, and retired from her opera career.

The de Chagny family and their intrigues and tragedies were taken from the real life Carpentier de Changy family, who counted among their ranks a Philippe, a Raoul, and an Eric! Leroux recounted an incident where the Vicomte and his brother fell in love with the same ballerina and fought a duel over it, leading to the death of one of the brothers.

Even the novel’s most mysterious character, the Persian, has his basis in a real person. Leroux’s backstory for him, as the daroga of Mazandaran, was completely fictional, but there really was a mysterious Persian man who dressed in an Astrakhan cap who attended the Paris Opera regularly. His true identity and past was unknown to most of the Parisian elites who saw him at the Opera, so Leroux was able to invent his history wholesale, but his real name was Mohamed Ismaël Khan. He was the son of Persian diplomat Hadji Khalil Khan, who was ambassador to India and was accidentally killed in 1802 by the bodyguards assigned to him from the East India Company. As part of Britain’s apology to the Shah, Ismaël was given a lifelong salary of 1,000 pounds a year. With this money, he lived in Paris and attended the opera regularly. He was the subject of many rumours and different stories over the years by Parisians eager for gossip and Orientalism.

Mohammed Ismaël Khan

Ultimately, Leroux’s years of experience as a journalist enabled him to craft a tale where the lines between fact and fiction are extremely thin, interweaving gossip with history and imagination. The effect when reading can be quite convincing, and has created a difficult mess to untangle for modern historians seeking the novel’s inspirations and trying to sort out the reality, now that we are more than a century removed from the publication of the novel and the events that it references.

1925 edition of the book promoting the movie

The 1925 film adaptation initially had a goal of staying extremely faithful to the original novel, and while that goal was strayed from over the course of re-shoots and re-edits, it remained the only adaptation that was even close over the next sixty years. Future film versions seemed largely unaware of Leroux’s novel and merely iterated on the basic idea, introducing elements that would become repeated like the Phantom’s disfigurement being caused by acid or fire, and the notion that the Opera House was stealing his music. Finally, the famous 1986 musical by Andrew Lloyd Webber returned to Leroux as the primary inspiration - possibly thanks to the fact that the book had fallen into public domain in the UK and US by that time. While the musical differs in many aspects, fans of the novel will recognize in both the 1925 film and musical many familiar characters and incidents, such as the falling chandelier, Masquerade, and so on.

1987 edition of the novel, promoting the musical

Over a century later, Gaston Leroux’s work has continued to inspire art and artists around the globe, forming a link between modern day works of music and storytelling with the music and stories of 19th century Paris.

Written by Ben Rowe.