L’Opéra Garnier

"Le Fantôme de l’Opéra a existé." The Phantom of the Opera did exist. So begins Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel, as the author crafted a careful and convincing fiction that the story was based on witness testimonies and true histories. Leroux was a journalist before he became a writer of mystery fiction, working as a court reporter and theatre critic, and during this period he made many contacts at the Théâtre National de l'Opéra and learned of the many rumours, gossip, and strange facts surrounding the building and its history. And so, many of the strange features of the Opera House in the story he created are not wild fancies of imagination, but true facts—the Phantom himself may not have been real, but many core aspects of the novel did exist.

The site of the building was chosen in 1860 during the Second Empire, and in December of that year the Emperor Napoléon III announced a design competition for the building. To the great surprise of Paris’s elite, the winner was not an established architect like Eugène Viollet-le-Duc or Charles Rohault de Fleury, but a relative unknown by the name of Jean-Louis Charles Garnier. Garnier’s design was selected for its “rare and superior qualities in the beautiful distribution of the plans, the monumental and characteristic aspect of the façades and sections.” When his design was criticized for not following any existing architectural style, Garnier ingratiated himself to his client by declaring the style to be “Napoléon Trois!”

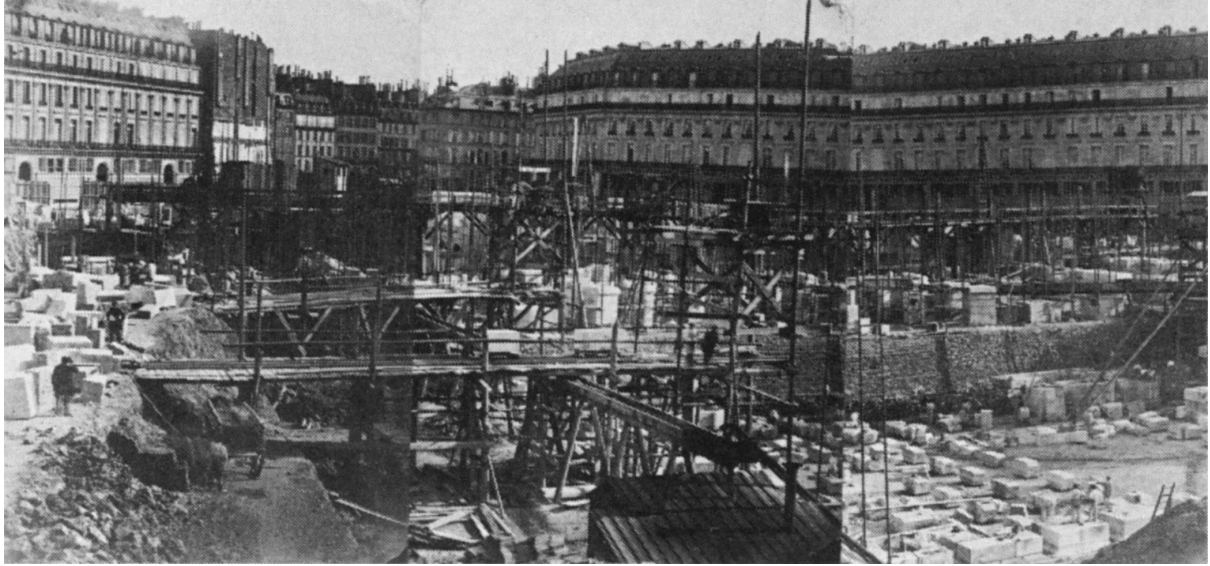

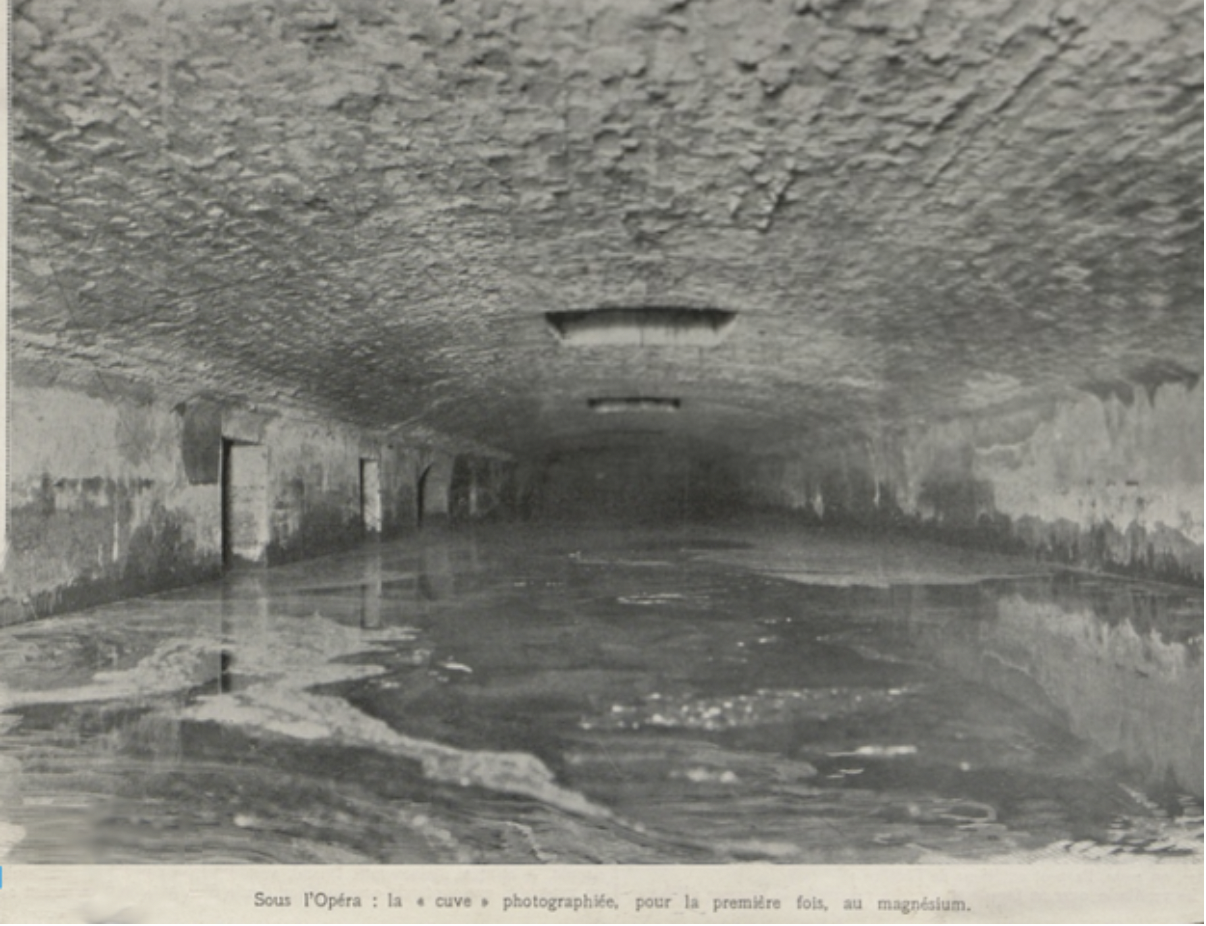

The laying of the foundation began in 1861 and had to be built exceptionally deep and strong—the size and scale of Garnier’s design meant that the foundation had to support a weight of nearly 10,000 tonnes, with deep basements to support all the cellars needed to store scenery, props, and more. It was known that the high groundwater of Paris would cause an issue in this regard, and ultimately, even with eight steam pumps operating twenty-four hours a day, they were not able to pump away enough water to prevent flooding during construction. Garnier’s solution was to build a cistern at the bottom of the foundation that would hold the groundwater and relieve pressure on the foundation’s walls, while also serving as a counterweight for the stage and a reservoir in case of fire.

Construction lasted for twelve years, suffering an interruption with the Franco-Prussian War that led to the Siege of Paris in 1870. Work had progressed to such an extent during the siege that the building found use as a military storehouse, holding food reserves and serving as a hospital. The Second Empire collapsed as the Emperor was captured by the Germans, and the National Guard, which had defended the city during the siege, became radicalized and took over the city, establishing their own government known as the Paris Commune. The Commune kept prisoners in the cellars, which run five levels deep beneath the building and became referred to as the “dungeons.” The Republican Army of the Third French Republic entered the city in May of 1871 and retook it from the Commune, with hundreds killed. In 1907, bodies were found buried in the cellars, possibly victims of the Commune or the Republicans. These morbid details contributed to the growing body of rumours around the building. When you know that people have suffered and died in the cellars, it’s not a large leap to start talking about opera ghosts.

The Third Republic was not particularly enthused with the elaborate, decadent building Garnier had designed for the Emperor, and it looked like Garnier’s vision might never be completed. But when the Paris Opera’s then-current venue, the Salle Le Peletier, burned down, the need for a new Opera House became critical, and Garnier was instructed to finish the building as quickly as possible.

The building was completed by late 1874 and inaugurated on January 5, 1875, and served as the home for the Paris Opera until 1989. Opera was the premier form of entertainment in continental Europe in the late 19th century, and the Paris Opera incorporated ballet into each production, such that operas that wished to perform there but did not have a ballet were required to add one to be featured.

The finished Opera House, known as the Opéra Garnier or Palais Garnier for its opulence, followed the “Napoléon III” style in leaving no surface undecorated. The building uses a dizzying array of materials and colours to present a stunning continuous work of art that overwhelms the senses with maximalism. The façade is filled with sculptures and mosaics, with the famous sculpture of Apollo and his lyre crowning the height of the roof. Apollo is in bronze, with his lyre in gold, and also serves a functional role as a lightning rod for the building.

The interior is an interweaving labyrinth of corridors, stairways, alcoves, and landings, designed to allow both the movement of performers and stagehands throughout the building unseen, as well as plenty of space for large audiences to stand and socialize during intermissions. The famous grand staircase in the foyer is marble and splits into two divergent flights leading up into the wings of the auditorium. Every surface is covered in sculptures, mosaics, paintings, murals, chandeliers, and other decorations.

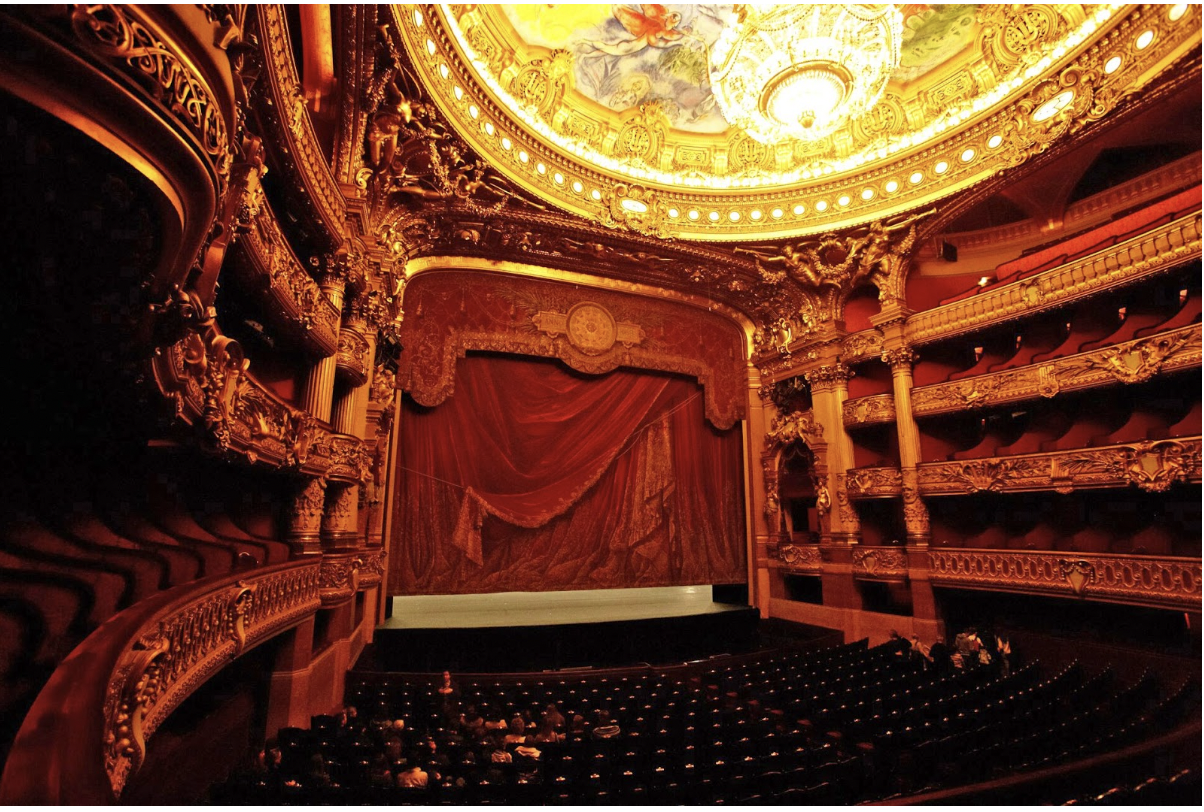

The auditorium is the largest in Europe, capable of seating nearly two thousand spectators and accommodating almost five hundred people on stage. The opera productions of the late 19th century were equally maximalist affairs, with elaborate sets, costumes, huge casts in the choir, and even elements such as live animals. The Opera House had stables where live horses were kept specifically for use in performances.

Perhaps the most famous feature of the auditorium is the seven-ton bronze and crystal chandelier, which alone cost thirty thousand gold francs. The use of a large chandelier in the auditorium was criticized by many as impractical and undesirable, as it blocked the view of the stage for patrons on the fourth level, but Garnier responded, “What else could fill the theatre with such joyous life?”

The opera was fitted with electric lights in 1881, and in the period of the story of The Phantom of the Opera (roughly 1884), the most popular opera performed there was Charles-François Gounod’s Faust. It is this opera that is being performed in both Gaston Leroux’s original novel and the 1925 silent film adaptation.

The labyrinthine passageways and myriads of people coming and going at all hours lent themselves well to rumours of a secret person hiding in the opera—rumours of an assistant of Garnier’s who asked as payment to be allowed to live in the secret passageways, for example. After all, theatre performers and technicians are a superstitious bunch!

But one incident in the Opera’s history can be definitely traced as an inspiration for Leroux’s novel: in 1896 an electrical short caused a cable to melt and drop one of the counterweights for the chandelier, crashing through the roof of the auditorium and landing on the audience, killing one and injuring seven others. This would inspire the crash of the chandelier that forms one of the main events in the novel.

Since 1989 the Paris Opera has split its time between the Palais Garnier and the modern Opéra Bastille, with modern works often performed at the newer venue and traditional works performed at the great landmark of Paris. The building remains a major tourist attraction and proudly plays off its association with Leroux’s novel—as Box Five is adorned with a small brass plaque: “Loge du Fantôme de l‘Opéra.”

Written by Ben Rowe.