Cinerama: Revolutionizing the Film Industry in the 1950s

In the early 1950s, the American motion picture industry was faced with a crisis. Every year theatre attendance was declining, as more and more homes gained a television set and the regular ritual of going to the movies began its slow march out of everyday life.

A number of gimmicks emerged in that decade to try and draw audiences back to theatres. The 1952 film Bwana Devil set off a cycle of 3D movies that burned out in only two years, but the innovations created by Cinerama had a much longer lasting legacy in the presentation of motion pictures. Cinerama was created by inventor Fred Waller and developed by journalist Lowell Thomas, producer Mike Todd, and filmmaker Merian C. Cooper. It was first successfully demonstrated by the 1952 documentary This is Cinerama. Inspired by earlier gimmicks like the wide screen created by the “triptych” finale of Abel Gance's film Napoléon in 1927, Cinerama sought to immerse audiences within the world of the picture using an ultra wide aspect ratio that engaged a viewer's peripheral vision.

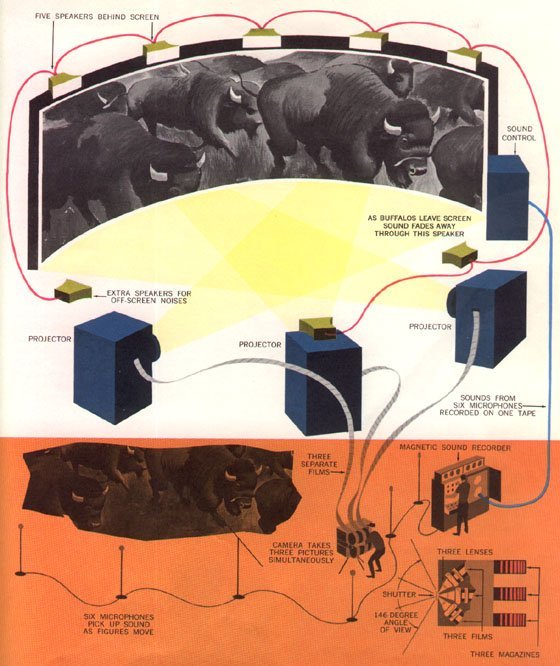

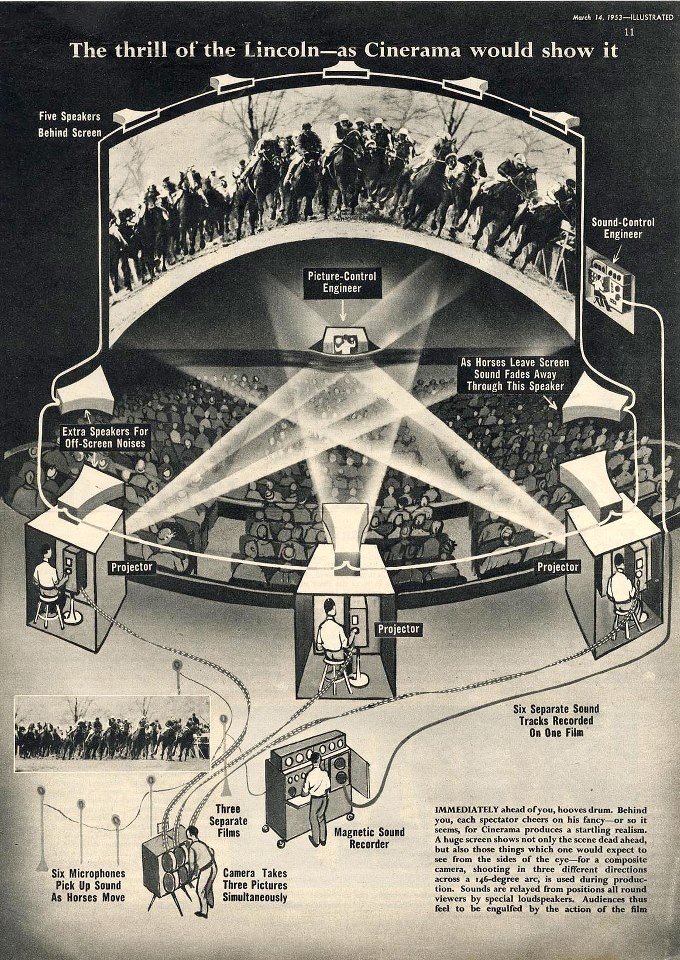

Typical American motion pictures before 1952 were shot in an aspect ratio of 1.37:1, or “Academy ratio”, giving a nearly square appearance to the motion picture frame. Cinerama sought to replicate the wide angle of human vision by using three 35mm cameras filming simultaneously to capture a 146 degree horizontal arc of vision. These three interlocked cameras used 27mm lenses which replicated the focal length of the human eye. In exhibition, the three film prints produced would be projected in synchronization by three projectors to produce a wide screen image with three times the image fidelity of a single film strip. The resulting aspect ratio was approximately 2.89:1.

The key innovation that differentiated Cinerama from past efforts was the introduction of a curved screen. Theatres equipped with Cinerama featured a massive screen which curved to the left and right of the audience, creating the illusion of peripheral vision. In order to sell the “you are there!” intent of the system, these theatres also employed a seven channel surround sound system unlike anything used in standard cinemas at the time.

This is Cinerama was a huge box office hit, and was followed by a series of Cinerama documentaries over the next decade which used the natural splendor of places like the Grand Canyon to great effect. Meanwhile, technologies like anamorphic lenses were developed to try and replicate the Cinerama effect on a smaller scale using single camera and single projector systems. Anamorphic widescreen, originally trademarked as CinemaScope by 20th Century Fox, produced an aspect ratio of 2.35:1 and eventually became a standard for large budget pictures, though it lacked the higher definition image of true Cinerama.

While Cinerama was an overwhelming technical achievement, it also presented a number of challenges to be presented properly. The original Cinerama screens had to be specially constructed to overcome the issue of light spill from one side of the screen to the other. The three projectors had to be kept in perfect synchronization, and the three images had to be perfectly aligned on the screen. The more that an audience became aware of the “seams” between the three images, the more disorienting Cinerama had the potential to be. The sheer expense of shipping three times the amount of film as a regular motion picture, with three times the potential for wear and tear to disrupt the illusion of the image, made the system impractical to implement on a large scale. At the height of the system's use, only 288 theatres could show a film in true Cinerama.

How the West Was Won, debuting ten years after This is Cinerama, was the first full length narrative feature film in the format. A massive epic, it nevertheless demonstrated through its production many difficulties with using the system for dramatic pictures, as the process made blocking scenes between actors difficult. The curved screen had to be taken into account to arrive at eye lines that would look natural to an audience even when they felt unnatural on set. Directors found their creativity boxed in by the needs of the technology – Cinerama could not deliver a close-up, for instance, and all shots had to be captured by the 27mm lens the system employed.

By the early 1960s, even the Cinerama venues were looking for a cheaper alternative that would still deliver something akin to the grandeur of true Cinerama. And so Mike Todd and his partners spurred the development of a number of 70mm film systems that would give ultra wide aspect ratios at improved visual fidelity due to the use of a larger film stock. While this required larger cameras and larger projectors, the result was high definition cinema without the major hassle of the three film Cinerama system. Films like Grand Prix (1966) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) were shot this way and then projected onto Cinerama screens in the twilight of the format.

Today, there are only four commercial theatres in the world still equipped to show true Cinerama in its original technical specifications. However, the concept of a large screen high fidelity cinematic experience lives on in formats such as IMAX, whose history mirrors Cinerama's in many ways from its origin in nature documentaries to its use in large budget feature films. While the Calgary Cinematheque's presentation of How the West Was Won (1962) at Contemporary Calgary's Centennial Planetarium is not precisely true Cinerama, it is a replication of an enthralling moviegoing experience that remains as rare as it is memorable.

Written by Ben Rowe.