Johan Grimonprez's Double Take (2009)

9:15pm, Thursday, May 19, 2011

Double Feature with The Birds

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A | 80 mins | English | B&W,Colour | 1.78:1 | 35mm The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

The Calgary Society of Independent Filmmakers and the Calgary Cinematheque are pleased to present an exciting double feature event in order to close out the Cinematheque's latest season! Join us for this captivating pairing of unconventional works and experience the thrill of Hitchcock as never before!

Double Take (Grimonprez, 2009) is a paranoid meta-movie that transgresses the lines of fiction and documentary and is perfectly paired with its shadow-film, Hitchcock's own sci-fi-realist 1963 shocker: The Birds.

Double Take

Johan Grimonprez's ingenious documentary/fiction hybrid—a meditation on identity, filmmaking, power and paranoia—looks at Alfred Hitchcock's late 50s and early 60s films against the climate of Cold War-era political anxiety. With it, Grimonprez traces the global rise of fear as a commodity, examining modern history through the lens of mass media, advertising and Hollywood: as television hijacks cinema, and the Krushchev and Nixon debate rattles on, sexual politics quietly take off and Hitch himself emerges in a dandy new role on TV, blackmailing housewives with brands they can't refuse. What's more, a plot of personal paranoia mirrors the political intrigue, in which Hitchcock and his elusive double increasingly obsess over the perfect murder—of each other!

A unique picture—and for once, that overused word fits—it's a sort of think piece on doppelgängers, the Cold War, Jorge Luis Borges, propaganda and the films of Alfred Hitchcock. And no, it's not likely to play your local multiplex any time soon.

For anyone interested in any of those subjects, though, it's worth a trip, and perhaps a good discussion with a friend over a cup of coffee afterward.

Basically, the film conflates a Borges essay with a fictional anecdote about Hitchcock who, in the midst of shooting The Birds, is called away for a phone call, and runs into his own double—actually, a future version of himself, gone back in time.

It's an odd, unsettling idea, and it's beautifully directed by Belgian filmmaker Johan Grimonprez, working in, essentially, mixed-media: bits of old Hitchcock trailers and TV shows, shots of a Hitch lookalike, narration from an impersonator, snatches of the Psycho score.

Edited with great invention and precision, it's a true treat for any Hitchcock buff, who will delight in the imaginative re-purposing of footage—a bit of Stage Fright here, some home-movie footage there—and fact—the director as a character in one of his own movies.

This isn't a normal movie; it's an art installation. And whatever it may have been meant to be, it takes its real meaning from you. -Stephen Whitty, Newark Star-Ledger, 2010

A Closer Look

"It relates to something very contemporary—the whole business of terrorist spectacle, the war in Iraq and nuclear proliferation with Iran. They are things in the background always shimmering…" -The Hitchcock effect

In his new film Double Take, artist and filmmaker Johan Grimonprez explores familiar themes: the way television manipulates audiences; induces a sense of fear; blurs the lines between fiction and reality. Again, at the centre of the film is that looming, jowly presence, Alfred Hitchcock. In a sense, the film is a companion piece to Grimonprez's short Looking For Alfred, which likewise played with the theme of the double by looking at Hitchcock's cameo appearances in his own films and envisaging what might happen if Hitchcock were to meet… Hitchcock. The difference about the new project is that the stakes have been raised. by Geoffrey Macnab

Flashback

to the early 1960s. It's the time of the Cuban missile crisis but also

an era where the rivalry between film and television is fierce. Cinemas

are closing down as the tube steals their audiences. Hollywood is in the

process of redefining itself. Hitchcock has already made Psycho with

his TV crew. He is about to start work on The Birds. At the

same time, he is creating a new image for himself as TV personality—the

man behind Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The Cold War is intensifying.

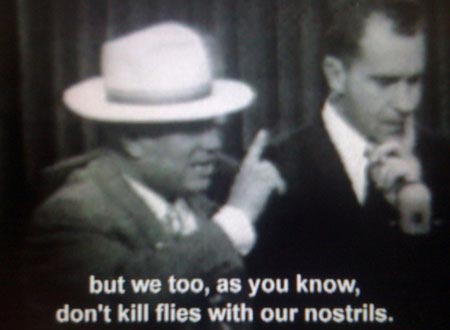

American audiences have watched Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and US

Vice-President Richard Nixon during their bizarre 'kitchen debate' on

TV—an encounter that plays today like a parody of an interview on the

Steve Allen or Milton Berle show. The two men are clowning. In a sense,

they are doubles of one another too. Despite their folksy chit-chat, the

threat is palpable. They are representatives of two global powers who

are ready to threaten one another with destruction.

Goosebumps

Double Take opens with accounts of an uncanny incident in the autumn of 1948 when hundreds of birds crashed into the Empire State Building and plummeted to the street. Next, we hear about a plane crashing into the Empire State. Hitchcock's film of The Birds was not, perhaps, as far fetched as it seemed. The fear felt about such freak incidences was to become more and more commonplace. Grimonprez contends that the sense of looming unease felt in the early 1960s is still with us today.

"The Birds is a metaphor for catastrophe television invading the home," Grimonprez muses. "Against, that, there is the historical backdrop of the missile crisis and the Cold War. That is a metaphor for doubles—the doubles of east and west, the political doubles of one another, both projecting fear but trapped in the same paradigm… it relates to something very contemporary—the whole business of terrorist spectacle, the war in Iraq and nuclear proliferation with Iran. They are things in the background always shimmering."

Hitchcock tapped into the sense

of dread that was in the society around him and used it to induce

goosebumps in his audience. Reduced to its essence, Grimonprez suggests

that this dread was all about fear of 'the other'. The media continues

to accentuate and prey this fear. In his film, there is a fictional

element too. He has recruited a Hitchcock lookalike, Ron Burrage, famous

for impersonating Hitchcock. At times, watching the film, we're not

sure where the archive footage ends or the imagery of Burrage begins.

Hijacking documentary

Double take also stands as a description of Grimonprez's working method which is to question received images and to turn clichés on their head. Meanwhile, the phrase also hints at what viewers have to do to make sense of the huge amount of images they are bombarded with on a daily basis.

Grimonprez first made his name internationally with his 1997 film, dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y, a hijacking documentary that many now feel to have been prophetic. The film was examining the voyeuristic fascination that terrorist hijackings exercised on viewers and the ingenious methods—sometimes closed to those used by avant-garde filmmakers—with which the news media filmed and presented their activities. The German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen famously described the events of 9/11 as "the biggest work of art there has ever been." His remarks provoked huge controversy and were taken out of context. Nonetheless, what Stockhausen called the "cosmic spirit of rebellion, of anarchy" was precisely what Grimonprez had been exploring in his documentary. He was looking at the way—as novelist Don DeLillo put it—the terrorist had usurped the role of the artist. "What terrorists gain, novelists lose," DeLillo wrote.

What were Grimonprez's own feelings during 9/11? "For me, the events were a confirmation of what was set forth in dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y,"

the director states. He remembers that at the time of the terrorist

attacks, he was breaking up with his then girlfriend. For him, the two

events became intertwined. He wasn't able to separate one incident from

the other. Somehow, the personal and the political meshed.

Grimonprez

Fear and voyeurism

Hitchcock's work and life provide Grimonprez with fertile territory to explore. With 'Hitch', fear and voyeurism, overlaps between the private and the public, go hand in hand. The British director understood far more quickly than his contemporaries that TV was consumed differently than films. The flow was constantly interrupted by commercials. Viewers could hop between channels and programmes. What is intriguing is how a filmmaker from Flanders like Grimonprez has ended up at the heart of US avant-garde filmmaking. Ask him about the trajectory of his career and the director admits that it has been an unlikely journey. Grimonprez was born in Roeselare, Belgium, in 1962. He came from a "simple Flemish family, with mum in the kitchen." He was educated at a Catholic school called Our Lady Of Joy. As a kid, he was interested in theatre. As an 18-year-old, Grimonprez declined to do National Service. He became involved with Amnesty International and with the burgeoning punk movement. "I think my mum and dad must have had a hard time," he says of his days as a teen rebel. "It was the moment of The Sex Pistols and The Clash." -Geoffrey MacNab is a UK journalist at The Guardian, The Independent.

Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds (1963)

The Calgary Society of Independent Filmmakers and the Calgary Cinematheque are pleased to present an exciting double feature event in order to close out the Cinematheque's latest season! Join us for this captivating pairing of unconventional works and experience the thrill of Hitchcock as never before!

Double Take (Grimonprez, 2009) is a paranoid meta-movie that transgresses the lines of fiction and documentary and is perfectly paired with its shadow-film, Hitchcock's own sci-fi-realist 1963 shocker: The Birds.

Making a terrifying menace out of what is assumed to be one of nature's most innocent creatures and one of man's most melodious friends, Mr. Hitchcock and his associates have constructed a horror film that should raise the hackles of the most courageous and put goose-pimples on the toughest hide. … and as is his fashion, he has constructed it beautifully, so that the emotions are carefully worked up to the point where they can be slugged. - Bosley Crowther, NYT, 1963

Alfred Hitchcock's most abstract film, and perhaps his subtlest, still yielding new meanings and inflections after a dozen or more viewings. As emblems of sexual tension, divine retribution, meaningless chaos, metaphysical inversion, and aching human guilt, his attacking birds acquire a metaphorical complexity and slipperiness worthy of Melville. Tippi Hedren's lead performance is still open to controversy, but her evident stage fright is put to sublimely Hitchcockian uses. -Dave Kehr, Chicago Reader

"What sets The Birds apart from the other films in Hitchcock's incredible ten-year run is its remarkable chilliness. Matt Bailey, 2005"

The film couldn't be simpler: birds attack humans. Hitch never provides an explanation or even a satisfactory conclusion to this problem. What's more, the first real attack doesn't come until around the film's halfway point, and yet the Master keeps us riveted throughout with his playful little hints. By the time The Birds reaches its climax, the tension and terror becomes almost joyously unbearable. -Jeffrey M. Anderson, 2006

Alfred Hitchcock's 1963 follow-up to Psycho (1960) is an ambitious adaptation of a Daphne du Maurier story. Groundbreaking on several levels of cinematic technique and dramatic form, The Birds combines forward-thinking special effects with an unconventional soundscape to instill a palpable lurking fear in the audience. Although not as horrifically shocking as Psycho, The Birds is a more sophisticated film, and represents a high watermark in the prolific career of a true maestro of cinema. -Cole Smithey, 2009

Hailed as one of Hitchcock's masterpieces by some and despised by others, The Birds is certainly among the director's more complex and fascinating works. Volumes have been written about the film, with each writer picking it apart scene by scene in order to prove his or her particular critical theory--mostly of the psychoanalytic variety. Be that as it may, even those who grow impatient with the slow build-up or occasional dramatic lapses cannot deny the terrifying power of many of the film's haunting images: the bird point-of-view shot of Bodega Bay, the birds slowly gathering on the playground monkey bars, the attack on the children's birthday party, Melanie trapped in the attic, and the final ambiguous shot of the defeated humans leaving Bodega Bay while the thousands of triumphant birds gathered on the ground watch them go. -TV Guide, 2007

"What he made was essentially the world's first conservationist horror picture … in the end, it's a movie that feels like it was made by a brilliant filmmaker who simply felt challenged by the enormity of the task. In that regard, it's close to 100 percent successful." -Ken Hanke, 2007

Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972)

7:00pm, Thursday, April 21, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

165 mins | Russian with English subtitles | B&W,Colour | 2.35:1 | 35mm

For those curious about Tarkovsky's wider impact on cinema and the world alike, Nostalghia.com is an incredibly detailed site devoted to the filmmaker—with quotes, links, bio info, and much, much more—all compiled locally (in Calgary) by Tarkovsky experts!

It holds up remarkably well as a soulful Soviet "response" to 2001: A Space Odyssey, concentrating on the limits of man's imagination in relation to memory and conscience. Sent to a remote space station poised over the mysterious planet Solaris in order to investigate the puzzling data sent back by an earlier mission, a psychologist discovers that the planet materializes human forms based on the troubled memories of the space explorers—including the psychologist's own wife, who'd killed herself many years before but is repeatedly resurrected before his eyes. More an exploration of inner than of outer space, Tarkovsky's eerie mystic parable is given substance by the filmmaker's boldly original grasp of film language and the remarkable performances by all the principals." - Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader

Often compared to Stanley Kubrick's great 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is, in fact, the opposite of 2001—a movie obsessed not with machinery but with its breakdown, not with mankind's evolution and end but with its stubborn immersion in the past." -Michael Wilmington, Metromix Chicago, 2003

The third feature in Tarkovsky's brief, shining career will deliver you from the mundane to the sublime. An extended, cinematic poem, Solaris transforms the elements of Polish writer Stanislaw Lem's 1961 novel into a Tolstoy-influenced, religious treatise on the human race. The film, which won the 1972 Cannes Special Jury Prize, is a series of encounters between humans and their fears, fantasies and faith—or lack thereof. This is not your high-budget ray-gun clash between space voyagers and slime-covered monsters.

Tarkovsky doesn't script so much as paint and compose; his work is a collection of living paintings, or visual symphonies, rather than narrative movies. Though Solaris is one of the late director's most plot-coherent and accessible films, its plot is still a mere conduit for mood, atmosphere and philosophy. -Desson Howe, The Washington Post, 1990

Nothing that's visible matters very much—except for nature: shots of a pond of water weeds of a running horse—and life's surface are quite unimportant. Because of it, the blockish camera work, the egg-like colors and the general visual poverty are almost irrelevant. What matters is the conversations, the problems they raise, the faces that reflect them, seen blurrily as if at the end of an all-night session.

The result must be viewed actively and with some effort. But if it is, the result is extraordinary enough to compensate. The film's great metaphors—the faces of Donatis Banionis as Kris, Natalya Bondarchuk as Hari and Yuri Jarvet as Snouth—involve us totally in the difficult mysteries. Like his Solarian sea, Mr. Tarkovsky has made ideas walk, breathe and move us. -Richard Eder, NYT, 1976

Tarkovsky

Unlike the films of other contemporary Soviet directors, those of Andrei Tarkovsky demonstrate a personal and original vision that placed him alongside Godard, Bergman, and Fellini as one of the major European filmmakers of our time. Tarkovsky "makes movies with an ambition and intensity" which has been virtually "absent from Soviet film for over 40 years," writes J. Hoberman of the Village Voice. British critic Ivor Montgu compares the striking images of Tarkovsky's films to Breughel's paintings (which are themselves quoted in Solaris), finely detailed compositions that have "beauty, harmony, and relevance... When one has seen any one of his films once, one wants to see it again and yet again." Tarkovsky's seven features and two shorts have each won numerous prizes at international festivals, including the Golden Lion at Venice, the Grand Prize at San Francisco, and at Cannes, the Special Jury Prize (twice) and the Grand Prize for Creative Cinema.

Andrei Tarkovsky was born in Moscow on April 4, 1932. His father, Arseni, was a well-known poet of the period. In Tarkovsky's own words, "During my high school period I attended the School of Music, and I did some painting. In 1952 I enrolled in the Institute of Oriental Languages, where I studied Arabic. All this wasn't for me." He left school to join a geological research group on an expedition to Siberia, where he remained for nearly a year and produced a whole series of drawings and sketches. Then, in 1956, he entered the State Institute for Cinema (VGIK), to study under Mikhail Romm.

While at film school, Tarkovsky made a short, There Will Be No Leave Today, and, for his diploma, the hour-long ̈The Steamroller and the Violin which, he notes, "was very important for me because it was there that I met the cameraman Vadim Yusov and the composer Vyacheslav Ovchinikov, with whom I have continued working." The script was by another school friend, Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovsky, who later wrote Tarkovsky's Andrei Roublev and went on to become an accomplished director himself (Siberiade, Runaway Train). The hero of The Steamroller and the Violin is a twelve-year-old boy who yearns to be a steamroller driver while he studies to play the violin. The film's themes of dissatisfaction with art as an end in itself, and a rejection of art as an elite occupation, reappear in the director's more mature works.

Tarkovsky's first feature, Ivan's Childhood, appeared in 1962 and was greeted enthusiastically around the world. Critics heralded the arrival of a great talent in the Soviet cinema after decades of creative stagnation. The Ivan of the title is a newly orphaned twelve-year-old who volunteers to fight the Nazis during World War II. His "childhood" is, instead, a perverted adult existence: Ivan serves as a spy who crosses enemy lines, and who one day fails to return. An epilogue reveals, through a file kept by the Germans in Berlin, that he was condemned to death and hanged. Jean-Paul Sartre described Ivan's Childhood as "socialist surrealism," and praised the remarkably complex and unsentimental approach Tarkovsky used for his melo-dramatic subject.

His next film, Andrei Roublev, completed four years later in 1966, is considered by many critics to be the one indisputable Russian masterpiece of the decade. Tarkovsky chose as his subject the life of Andrei Roublev, the great Russian icon painter of the Middle Ages. Reliable historical information on Roublev is scarce, so Tarkovsky invented his own vision of the past, demystifying the reverence of popular legends. Shooting the film in widescreen black and white, he depicts Roublev as a despairing humanist in a brutal world. He observes shocking atrocities committed by feudal lords and invading Tartars, as well as an erotic pageant of uninhibited pagans, frolicking in the nude. In time, he abandons all hope, vowing to remain silent and to stop painting.

Many years later, when a local duke seeks a craftsman to build him a bell of unprecedented size, a young boy answers the call. Claiming to be the son of an artisan who taught him the secrets of the craft before he died, the boy (Kolya Burlyayev, who also played the role of Ivan) sets out to build his duke a masterpiece. Despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles, the bell is flawlessly completed, and it rings throughout his village. Overcome with joy and released anxiety, the boy confesses to Roublev that he had lied and that he had constructed the bell with no prior expertise. A greatly moved Roublev, breaking many years of silence, comforts the boy and tells him that as artists they will work together. A montage of his icons, in vibrant color, closes the over-three-hour film. Andrei Roublev was held up for general release by the USSR until 1971, causing a scandal, and much speculation in the West. Some observers believe the Russian censors were shocked by the violence, eroticism, and the obsession with religion, all unorthodox for the Russian cinema of the day. In 1969 the film won the International Critics Prize at Cannes, and in 1973 it made its US debut—in a cut version later restored and released by Columbia Pictures but presently no longer available—at the New York Film Festival.

Tarkovsky turned to a novel by Polish science fiction writer Stanislaw Lem for his third feature, Solaris, released in 1972. Three years later, he completed The Mirror, a film more directly autobiographical than any he had made before or since. "It is the story of my mother and thus part of my own life," he has said. "The film contains only genuine incidents. It's a confession." Tarkovsky's parents separated in 1935, and The Mirror has been seen as his way of exorcising repressed feelings from his childhood. Voice-over readings of his father's poems and other, unusually subjective associations lead the viewer through a labryinth of scenes and images. Soviet authorities disapproved of The Mirror and its domestic release was restricted. While Western critics might point to the influences of Bergman and Resnais and their deeply introspective themes, or to Fellini's 8 1/2 as an example of a director's self-appraisal, Russian critics have no such vantage point within their national cinema.

Tarkovsky returned to science fiction in his next film, Stalker (1979), loosely based on a 1973 novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. The novel was set in North America; Tarkovsky transferred the story, without actually specifying its locale, unmistakably back to Russia. Taking place in the future, Stalker concerns a government-restricted, mystery-shrouded area known as the "Zone," at the center of which exists a "Room" where wishes are fulfilled. The hazards of the unpredictable Zone can only be avoided if one travels with a "stalker," who will illegally guide the uninitiated. Living on the Zone's periphery, with dirty clothes, shaven head, and a decrepit family, Tarkovsky's stalker resembles a political prisoner in a work camp. He is hired by two intellectuals, an unnamed scientist, and a writer, to reach the Room. "In the end," critic Gilbert Adair writes, "the scientist, denouncing the false hopes the Room must encourage, toys with the notion of blowing it up, while the writer, who sought to spur his flagging creativity, contemptuously declines even to formulate a wish. To the wretched, by now half-demented stalker is left the Sisyphian task of sustaining a doubtful faith of which he is a humble priest but without which he is nothing."

Tarkovsky's next film, Nostalgia, was to be his first with footage shot outside the USSR and his first collaboration with a non-Russian crew. In the end, because of difficulties encountered with the state agency Sovinfilm, virtually all of Nostalgia was shot in Italy. Tarkovsky's cultural hybrid was greatly assisted by veteran Italian screenwriter Tonino Guerra, who spoke fluent Russian and whose wife is Russian. The sometimes elusive narrative concerns a Russian scientist (not coincidentally also named Andrei) who has come to research in Italy.

His travels across the landscape, in the company of his guide, a tantalizingly beautiful young woman, are inevitably suffused with a growing sense of spiritual melancholy and "nostalgia" for his distant homeland. He meets a perhaps-mad recluse named Domenico, played by Ingmar Bergman regular Erland Josephson, whose eerie, mystical pronouncements touch on the fragile nature of faith in the modern world, which he seeks to re-affirm in a shocking act of self-immolation. Andrei, both the protagonist and the filmmaker, attempt to emulate the spirit of Domenico's tragi-heroic act in a climactic scene of spectacular, severe beauty.

The Sacrifice, filmed in Sweden with Sven Nykvist behind the majestically tracking camera, and unveiled at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival, turned out to be Tarkovsky's last testament. Not unlike his previous film, its restless protagonist (again played by Erland Josephson) is confronted with the dilemma of just how strongly felt is one man's belief in his ideals—is he willing to act on them? The onset of a nuclear war—not seen but overheard via radio announcements and the sound of planes and rockets overhead—compels him to an act of "sacrifice" that tears at the roots of his considered, almost bucolic daily life, yet also stands as a protestation of faith and hope for its future.

Andrei Tarkovsky died of cancer on December 28, 1986. Among the many posthumous tributes was one by Sight and Sound critic Peter Green, which concluded:

"A successor to his own Roublev, a commentator on our modern condition, an icon painter in film, and a man of profound belief, it was Tarkovsky's aim to bring the inward, spiritual world into a state of harmony with the outward, material world. Perhaps more than any other, he perceived the potential of film for charting the modern space-time dimension we inhabit."

Daniel Cockburn's You Are Here (2010)

Alberta Premiere

7:00pm, Tuesday, April 12, 2011

Calgary Cinematheque sponsored event

The Plaza Theatre›1133 Kensington Rd NW›

78 mins | English | Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

"A charming, Charlie Kaufman-like metafictional puzzler." -Leslie Felperin, Variety

A borgesian fantasy composed of multiple worlds, You Are Here circles and weaves around itself in unexpected ways. At the centre of this narrative labyrinth is Tracy Wright (Me And You And Everyone We Know, Monkey Warfare), a reclusive woman who searches for meaning in the mysterious documents that keep appearing to her. Her investigation begins when she finds a tape recording of a man giving a bizarre lecture: calming and sinister at the same time, he instructs how to "get where you need to go." One by one documents present themselves to create a puzzle of space and mind. You Are Here follows several interwoven characters, and puts viewers in a state of disorientation, taking them from one story to another.

You Are Here is the first feature film by internationally acclaimed Toronto-based video artist Daniel Cockburn. Funny, disturbing, and thought-provoking, it pushes at the boundaries of cinematic storytelling—while creating a deep and strange emotional connection with its cast of characters as they negotiate an absurd and cryptic world.

"Inventive and multi-layered, You Are Here is a brilliantly organized first feature full of philosophical ideas and tremendous energy." -Atom Egoyan

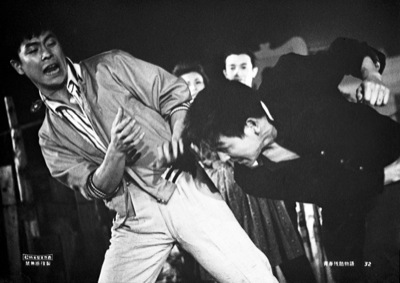

Nagisa Oshima's Cruel Story of Youth (1960)

7:00pm, Tuesday, April 5, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

12:00pm, Saturday, April 9, 2011

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

96 mins | Japanese with English subtitles | Colour | 2.35:1 | 35mm

"There are few color prints being shown in our first-run theaters that are as rich as this one.Vincent Canby, 1984, New York Times"

Last in the series—and least only in age—is Nagisa Oshima: the audacious youngster who pushed the formal and social limits of existing Japanese cinema to the point of utter rejection. He challenged audiences with attacks on every kind of zeitgeist, rebelled against whatever dogma he could identify, and made colourful, wide-screen films that simultaneously reflected and bequeathed the changing social atmosphere of the early 1960s.

These traits are all readily found in his Cruel Story of Youth (1960); with a narrative revolving around a pair of outcasts partaking in questionable activities in even seedier turf, the film manages to deconstruct and interrogate social norms while retaining a vibrant, energetic, provocative tone. It practically defines the Nuberu bagu—Japan's New Wave—and thus stands as a definitive work in the nation's already crowded list of genuinely outstanding movies.

Nagisa Oshima's Cruel Story of Youth did more than any other movie to establish the notion of a Japanese new wave. On its home ground, the director's third feature must have seemed like a local Rebel Without a Cause—it's set in a student milieu, populated by teenage gangs, and driven by adolescent risk-taking. As filmmaking, this wide-screen, candy-colored extravaganza is directed with considerable brio and filled with bold metaphors. Oshima splatters his title credits on a newspaper and films a scene against an actual student demonstration. His alienated antihero pushes the provocative antiheroine into polluted water as a prelude to satisfying her sexual curiosity. (Later, they celebrate their love by riding a stolen motorbike into the ocean.) -J. Hoberman, 1999, Village Voice

Francis Leclerc's Looking for Alexander aka Mémoires affectives (2004)

9:00pm, Friday, March 18, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A | 100 mins | French with English subtitles | Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

Following an accident, veterinarian Alexandre Tourneur (Roy Dupuis) not only develops amnesia, but also acquires another memory and another language. He must try to reconstruct his past life out of the truths, lies and omissions provided to him by his family and friends. On trying to return to his origins, he stumbles upon a childhood trauma that he had never wished to remember, and which gives new meaning to the two mottos of Quebec and Ontario: Je me Souviens and Yours to Discover. The film is at the same time a moving homage to the indigenous cultures which we have wished to reject and to forget.

Francis Leclerc (b. 1971)

Francis Leclerc is the director of Une jeune fille à la fenêtre (A Girl at the Window, 2001), Mémoires affectives (Looking for Alexander) and most recently, Un été sans point ni coup sûr (A No-Hit, No-Run Summer, 2008). In 2005 he won Genies in the categories of Best Direction and Best Original Screenplay for Mémoires affectives, as well as the Jutra award for Best Direction.

Xavier Dolan's I Killed My Mother aka J'ai tué ma mère (2009)

7:00pm, Friday, March 18, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A - Coarse Language,Sexual Content,Substance Abuse

96 mins | French with English subtitles | B&W,Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

Teenage Hubert (Dolan) lives in the suburbs with his mother (Anne Dorval), who drives him crazy. Her kitsch decor, her tacky sweaters, even the way she eats her toast mortifies and enrages him. She, in turn, is humiliated when she hears for the first time of his sexuality from his new boyfriend's more acceptably middle-class mother. Dolan wrote the script for this film about the tormented love between mother and son when he was sixteen, and then produced, directed and starred in it. In addition to the three awards from the Directors' Fortnight at Cannes, the film received a number of awards internationally, as well as the Claude Jutra Award for the best first feature at the 2009 Genies.

Xavier Dolan (b. 1989)

Dolan is the current wunderkind of Canadian cinema, winning three awards at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival when he was only 19. His second film, Les Amours Imaginaires (2010) premiered to wide acclaim at Cannes and won the top prize at the 2010 Sidney Film Festival. He is currently working on a third feature, Laurence Anyways, and supplies the voice of Stan for the French language version of South Park.

Robert Morin's The Negro aka Le nèg' (2002)

9:30pm, Thursday, March 17, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A - Violence,Crude Coarse Language

92 mins | French with English subtitles | Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

This harrowing feature is typical of Robert Morin's dark, pessimistic views on crime, punishment and human suffering. A young black man is caught smashing a racist lawn ornament in rural Quebec, and terrible events ensue. The film offers a highly stylized take on rural racism, poverty and cultural dispossession, taking its colour palette from the brightly coloured ornaments at the heart of story. The film's Roshomon-inspired retelling of the night's crimes depends for its success on the acting of some of the greats of Quebec television and theatre, in particular Béatrice Picard (Cédulie) and Emmanuel Bilodeau (Canarde Plourde).

Robert Morin (b. 1949)

Robert Morin is the director of many films, including most recently Journal d’un coopérant (Diary of an Aid Worker, 2010); Papa à la chasse aux lagopèdes (Daddy Goes Ptarmigan Hunting, 2008); Que Dieu bénisse l’Amérique (May God Bless America, 2006); Windigo (1994); and Requiem pour un beau sans-coeur (Requiem for a Handsome Bastard, 1992), which won Best Canadian Feature at the Toronto International Film Festival. He is also one of founders of La Coopérative de Production Vidéo de Montréal.

Pierre Falardeau's February 15, 1839 aka 15 février 1839 (2001)

7:00pm, Thursday, March 17, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A | 120 mins | French with English subtitles | Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

This

scrupulously accurate historical film, based on the letters of Thomas

Chevalier de Lorimier, recounts the last day of the Patriots of the

Revolution of Upper and Lower Canada, before their hanging by the

British authorities on 15 February 1839. An intimate, stylish film, it

shows in a timeless way the nationalist aspirations of the francophone

and Canadian minorities under British colonization, and the universal

dimension of the questions that are always brewing in nationalist

movements, the desire for freedom and the courage individuals must have

to make the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of their dreams. 15 February

1839 is Pierre Falardeau’s most accomplished and most artistic film, in

which the question of dying with courage and dignity for a cause that is

almost certainly lost is addressed with a profound sense of humanity.

Pierre Falardeau (1946-2009)

Pierre Falardeau was a colourful and controversial director and an advocate for Quebec independence. He was the maker of populist film fare, such as the Elvis Gratton movies and The Party (1990), but also of highly polemical takes on Canadian history, most notoriously, Octobre (1994). This treatment of the October crisis and the FLQ was criticized by some as an apology for terrorism.

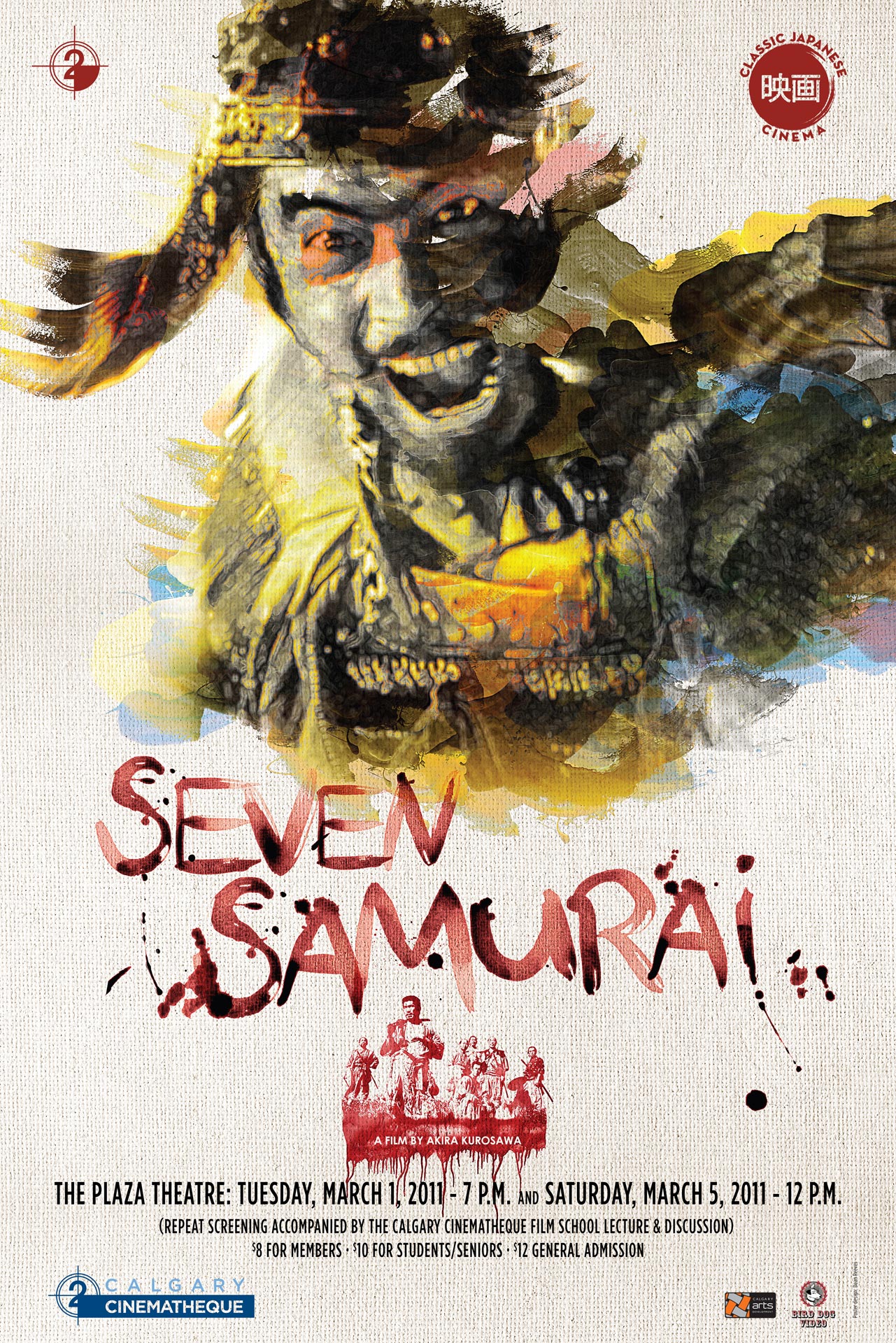

Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (1954)

7:00pm, Tuesday, March 1, 2011

12:00pm, Saturday, March 5, 2011

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG - Violence | 207 mins | Japanese with English subtitles | B&W | 1.37:1 | 35mm

Quite the change of pace, Kurosawa's Seven Samurai harnessed the action genre like no-one in 1954 had before. By alternating between multiple cameras, and casting Toshiro Mifune as the comical seventh samurai, the pacing is fresh, rapid, and involving—despite the 207-minute runtime. As the largest Japanese production of its day, Kurosawa was able to exploit vast custom built sets (like a purpose-built island village), and had access to a wealth of equipment with which to innovate. And innovate he did—Seven Samurai is the faraway source of a great many of the staples of today's action movies.

Breathtaking, fastmoving, and overflowing with a delightfully self-mocking sense of humor, Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai is one of the most popular and influential Japanese films […] Kurosawa adds a special flavor to the proceedings that sets them apart from any action film ever made. For the story of Seven Samurai isn’t one of simple Good versus Evil, as we learn when we’re told that these villagers have, in the past, preyed on the very class of samurai they’re now asking for help. And why are these samurai helping them, for virtually no pay, and with only a few handfuls of rice for food? Why, for the adventure of it all, of course. These men have seen many battles, but only in this one will they be truly able to test themselves. There’s no reward, and the odds against their winning are a good one hundred to one—and that’s exactly why they want to stay and fight. For these seasoned warriors long to experience that very personal sense of “honor” so prized by the Japanese. -David Ehrenstein, 1999, Criterion

"The movie is long, with an intermission, and yet it moves quickly because the storytelling is so clear, there are so many sharply defined characters, and the action scenes have a thrilling sweep." -Roger Ebert, 2001, Chicago Sun Times

Jia Zhang-ke's I Wish I Knew aka Hai shang chuan qi (2010)

7:00pm, Thursday, February 17, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG - Mature Subject Matter | 118 mins | Mandarin with English subtitles | Colour | 1.78:1 | Blu-ray

"I Wish I Knew is a love letter to the city and people of Shanghai.Liz Braun, 2010, QMI Agency"

The Calgary Cinematheque is pleased to announce a screening of Jia Zhang-ke's I Wish I Knew, his powerful, playful and ravishing new documentary about Shanghai. Zhang-ke has emerged in recent years as a master of world cinema and the leading face of the so-called 'sixth generation' of Chinese cinema. His previous films, such as The World (2004), Still Life (winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, 2006), and 24 City (2008), look at industrialization, globalization, and the changing face of China, often via China's changing landscapes. I Wish I Knew carries on that exploration in a more focused way, looking at the turbulent history of a mythical city.

Originally commissioned by the Chinese government for the 2010 Shanghai World's Fair, I Wish I Knew is a loving portrait of a city that is the site of significant political, criminal and artistic activity. Gloriously shot images of landmark sites such as Victoria Harbour and the Expo grounds serve as backdrops to stories of a city in constant change, most often stories of exile or arrival. Zhang-ke interviews people who experienced the momentous changes wrought by the Communist victory in 1949 and the Cultural Revoution of the 1960s, as well as people who worked on some of the many famous films made about the city, by directors such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, Wong Kar Wai and Michelangelo Antonioni. Reminiscences of the city are interspersed with clips from these films, along with more poetic sequences of the actress Zhao Tao wandering through some of Shanghai's contemporary industrial landscapes.

In the film, Shanghai emerges as a city as much of the imagination as of reality; a gateway to China and to the world; and the witness to some of the most profound political and economic changes of the twentieth century.

"What's most striking aren't the actual stories or Jia's masterful filmmaking, the subtle sound collages, the perfectly shot street footage, or his deliberate pacing. Instead, it's simply the film's rarest of rare qualities—its consistent, underlying maturity." -Guy Dixon, 2010, The Globe & Mail

Yasujiro Ozu's Tokyo Story (1953)

7:00pm, Tuesday, February 1, 2011

12:00pm, Saturday, February 5, 2011

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

G | 136 mins | Japanese with English subtitles | B&W | 1.37:1 | 35mm

"This remains one of the most approachable and moving of all cinema's masterpieces." -Wally Hammond, 2010, Time Out London

Of all the Japan-born directors of the Post-War period, Yasujiro Ozu is most often cited as having the most 'Japanese' style. In truth, this actually held back his films from being released in the Western world, since distributors were afraid his work would be too poorly received. On the contrary: he is now considered a remarkably significant figure in Japanese cultural history, perhaps second only to Kurosawa.

His Tokyo Story from 1953 aided Rashomon in welcoming the world's cinephiles to Japanese film style—with its immobile camera, long takes from low heights (Ozu developed the characteristic 'tatami shot'—a frame captured from about eye-level height when kneeling on a tatami mat), as well as fundamentally breaking established continuity editing rules. The film's plot is a (misleadingly) simple tale of a reluctantly hosted family visit that ultimately questions and complicates our perception of parenthood. Calmly, elliptically, revealingly, it somehow paradoxically unfolds as one of the screen's truest ever stories.

The capricious way in which this film entered world film culture might make us suspect that its success is accidental. Surely Late Spring (1949) and Early Summer (1951), to cite only two examples, are no less excellent? Ozu himself hinted at a reservation: “This is one of my most melodramatic pictures.” Yet Tokyo Story turns out to be a remarkably replete introduction to his distinct world. It contains in miniature a great many of the qualities that enchant his admirers and move audiences, no matter how distant, to tears.

There is, first of all, the mundane story. Ozu and his scriptwriter, Kogo Noda, often centered their plots upon getting a daughter married, a situation around which an array of characters’ lives could be revealed. But Tokyo Story lacks even this minimal plot drive; it carries to a limit Ozu’s faith that everyday life, rendered tellingly, provides more than enough drama to engage us deeply. An elderly couple leave the tiny town of Onomichi to visit their children and grandchildren. Inevitably, they trouble their hosts; inevitably, they feel guilty; inevitably, the children cut corners and neglect them. In the course of the trip, the old folks become aware of both the virtues and vanities of their offspring. On the train ride home, the mother is stricken, and shortly thereafter, she dies.

Tokyo Story also exemplifies Ozu’s unique style—low camera height, 180-degree cuts, virtually no camera movements, and shots linked through overlapping bits of space. In dialogue scenes Ozu refuses to cut away from a speaking character; it’s as if every person has the right to be heard in full. Other films use his distinctive techniques more playfully, but here he seems chiefly concerned with creating a quiet world against which his characters’ personalities stand out.

Thanks to Ozu’s compassionate detachment, the final scenes take on enormous richness of feeling as we watch characters contemplate their futures. Noriko smilingly tells Kyoko that “life is disappointing”; Shukichi assures Noriko that she must remarry; the neighbor jovially warns Shukichi that now he’ll be lonely. Yet the momentous revelations are tempered by the poetic resonance of everyday acts and objects. Shukichi greets a beautiful sunrise—signaling another day of brisk fanning and plucking at one’s kimono. An ordinary wristwatch links mother, daughter, and daughter-in-law in a lineage of hard-earned feminine wisdom. And the roar of a train dies down, leaving only the throbbing of a boat in the bay. -David Bordwell, 2003, Criterion Collection

Abbas Kiarostami's Through the Olive Trees (1994)

7:00pm, Thursday, January 20, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG | 103 mins | Persian with English subtitles | Colour | 1.85:1

Hossein Rezai, a nonprofessional actor with soulful eyes and a streak of stubbornness that is as big as his ego, plays a love-smitten bricklayer whose would-be fiancee (Tahereh Ladania) refuses to acknowledge his existence. Complicating matters is the fact that the two have been cast as newlyweds in a movie about earthquake survivors in northern Iran. [The film thus] combines a panoramic visual beauty with an acute sense of human tininess in the face of eruptive natural forces. -Stephen Holden, 1994, NYT

To call the pacing slow would be grossly understating the case—glacial would be more descriptive when Kiarostami demonstrates take after take after take of the same scene, to the point that we gain the director's point of view and feel like throwing up our hands when an actor screws up. -John Nesbit, Old School Reviews

On a deeper level, as the film begins to fade from memory, it seems to be asking unanswerable questions about the differences between a movie and reality (life as art) and questions the problems faced by filmmakers as they try to tap into cinema's unexplored potential. -Dennis Schwartz, 2006, Sover.net

Had things moved faster, numerous subtle and intricate touches would have been lost. The characters are all marvellously realized, and their interaction is so unforced that it draws the viewer in and puts the audience right next to the actors.

Moments of comedy are sprinkled throughout, often relating to the difficulties experienced by the director of the film-within-the-film as he attempts to get uncooperative performers to complete a take.

The film's ending is open to interpretation and reminds us that movies are only windows into another reality, and it's possible for them to close at the most inopportune times.

Overall, an exceptionally well-crafted and thoughtful motion picture. -James Berardinelli, 1995, ReelViews

Rather than explore the fiction/reality/documentary conundrum abstractly, as many other films have done, Olive Trees uses its naive, non-pro actors to draw a straight line between the audience and the real-life inhabitants of the area. The power of the film lies in the masterful way this is accomplished. -Deborah Young, 1994, Variety

Kenji Mizoguchi's Ugetsu (1953)

7:00pm, Tuesday, January 4, 2011

12:00pm, Saturday, January 8, 2011

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

The Plaza Theatre›1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG | 94 mins | Japanese with English subtitles | B&W | 1.37:1 | 35mm

Even Kurosawa looked up to Kenji Mizoguchi. Born in 1898, Mizoguchi was already experienced in directing by the time the War was over, and was heralded by Cahiers du cinéma writers like André Bazin and Jacques Rivette because of his expert usage of objective-reality-championing long-takes and mise-en-scène. He had previously perfected his (self-explanatory) shooting style: 'one shot – one scene,' but it wasn't until 1953—only three years before his death—that he used it in crafting his most celebrated film: Ugetsu monogatori.

Shortened in Anglicization, the title translates as 'Tales of Moonlight and Rain,' referring rather aptly to the film's subject matter and atmosphere. Focusing on two peasant couples in 16th century Japan, the film chronicles personal obsessions and family life via rather unconventional means: a ghost story. Adding to its allure, the film shadows the line between striking realism and lyrical otherworldliness, which, along with the continual movements of its crane-mounted camera, creates a breathtaking flow of complexity amidst subtlety.

"Film language that seems to create the mood it considers; the story and its style of telling are of one piece." -Roger Ebert, 2004, Chicago Sun Time

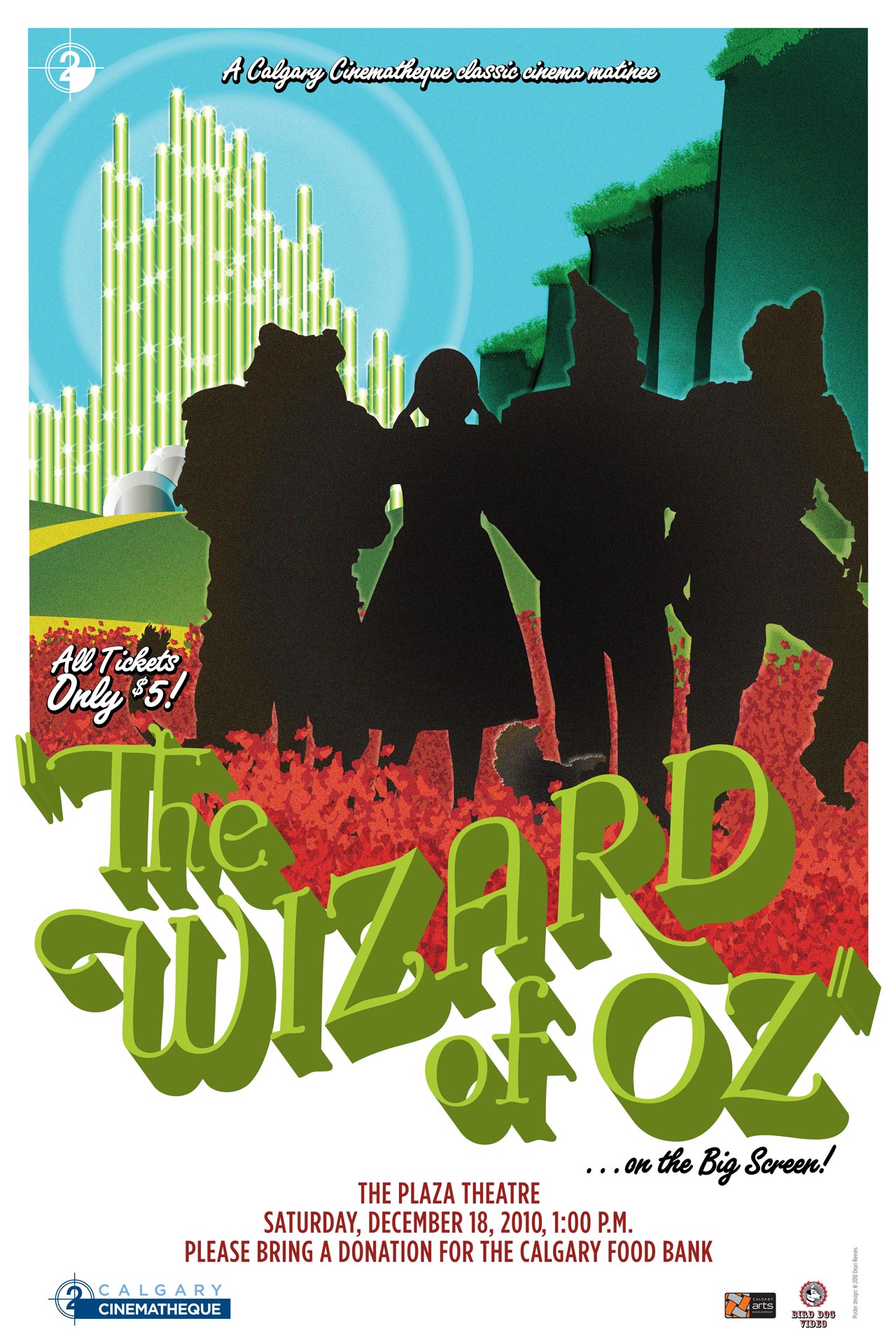

Victor Fleming's The Wizard of Oz (1939)

1:00pm, Saturday, December 18, 2010

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$5 Admission for ALL!

Please bring a donation for the Calgary Food Bank

PG | 101 mins | English | B&W,Colour | 1.37:1 | Blu-ray

"Is there another family movie as timeless as this one?" -Kevin N. Laforest, 2002, Montreal Film Journal

It's impossible to watch The Wizard of Oz today without feeling, within minutes, some kind of mystical connection to people you will never know. When Judy Garland sings "Over the Rainbow," there's the sense of participating, just by watching, in some beautiful shared human experience.

Today, in the days of home video, a child can watch The Wizard of Oz around the clock on a five-foot plasma screen. Yet it was scarcity that gave that earlier experience its value: You knew this was your only chance to see the movie for an entire year (and when you're 5 years old, a year is an eternity). And you knew—and this was a big part of the excitement—that other people were watching it, too. You could feel it.

Anyway, the entire sequence, from Dorothy's arrival in Oz to her departure on the Yellow Brick Road, has to be one of the greatest in cinema history—a masterpiece of set design, costuming, choreography, music, lyrics, storytelling and sheer imagination. -Mick LaSalle, 2009, San Francisco Chronicle

Don't miss this restored 1939 classic. There's nothing to beat the incredible sugar-rush of that shift from sepia-monochrome to full colour as Dorothy realises she's not in Kansas any more. It's a movie that speaks of Hollywood's unacknowledged fascination with the exotic, the mad, the unreal. Despite its earnest endorsement of the idea that there's no place like home …well, frankly there are plenty of places like boring old home, but nothing's like Oz. It's a wonderful trip behind the lines of thinkability, and the talking apple trees that slap you when you try to pick their fruit are the equal of anything in Lewis Carroll. A solid-gold Christmas treat. -Peter Bradshaw, 2006, The Guardian

This wonderful romp of a movie looks magical on the big screen: colors are a picnic for the eyes, details loom so clearly you can practically touch them and there's a sense of the larger-than-life with a film that's already larger than life.

And with an audience, it's a treat to watch Dorothy and Co. skipping down the Yellow Brick Road. The film hasn't played in theaters for more than 25 years, which means a couple of generations have missed the magic of seeing it as a social event in theaters. -Peter Stack, 1998, San Francisco Chronicle

A delightful piece of wonder-working which had the youngsters' eyes shining and brought a quietly amused gleam to the wiser ones of the oldsters.

And the circumstances of Dorothy's trip to Oz are so remarkable, indeed, that reason cannot deal with them at all. It blinks, and it must wink, too, at the cyclone that lifted Dorothy and her little dog, Toto, right out of Kansas and deposited them, not too gently, on the conical cap of the Wicked Witch of the East who had been holding Oz's Munchkins in thrall. Dorothy was quite a heroine, but she did want to get back to Kansas and her Aunt Em; and her only hope of that, said Glinda, the Good Witch of the North, was to see the Wizard of Oz who, as every one knows, was a whiz of a Wiz if ever a Wiz there was. So Dorothy sets off for the Emerald City, hexed by the broomstick-riding sister of the late Wicked Witch and accompanied, in due time, by three of Frank Baum's most enchanting creations, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman and the Cowardly Lion.

The [fantastical elements] are entertaining conceits all of them, presented with a naive relish for their absurdity and out of an obvious—and thoroughly natural—desire on the part of their fabricators to show what they could do. -Frank S. Nugent, 1939, New York Times

"A movie like this is so exhilarating, because, if you look deeper into it and go beyond its status, you find that it's more than just a musical lark.Joe Baltake, 2000, Sacramento Bee" "The Wizard of Oz is rarely seen on a big screen, and for that reason alone I urge you to go. But it also offers a chance, yet again, to see why The Wizard of Oz remains the weirdest, scariest, kookiest, most haunting and indelible kid-flick-that's-really-for-adults ever made in Hollywood." -Owen Gleiberman, 1998, Entertainment Weekly

Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927)

Complete 2010 Restoration · Alberta Premiere · One Night Only

Live musical accompaniment by the world renowned

Alloy Orchestra

7:15pm, Thursday, November 18, 2010

Accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra

The Uptown Stage & Screen›610 8th Ave SW

$25 Members/Students/Seniors / $35 General Admission

PG | 145 mins | Silent with English subtitles | B&W | 1.33:1 | HDCam

"A mad masterpiece that can only be truly appreciated on a big screen." -Leonard Maltin, 2010, Indiewire

Of all of cinema's master works, few have endured as tumultuous and rich a history as Fritz Lang's Metropolis from 1927; some 30 of its debut 153 minutes were thought forever lost, but now, thanks to two prints recently discovered in disparate film archives, only eight minutes remain unaccounted for. In virtually its original state, the prominent release of a digitally restored version earlier this year seems all but fated given how neatly it coincides with the Alloy Orchestra's own 20th anniversary—Metropolis being one of their longest-running and self-proclaimed "best loved" live accompaniments. And the revamping of their score to suit the freshly discovered footage has thus far received no less acclaim than Lang's own spectacular and oft-celebrated film.

Born in Vienna, Austria as Friedrich Christian Lang (1890–1976), his directorial career spans a staggering number of genres, and undertakes both social criticism and popular entertainment alike—each instance steeped in his unique approach of resolute yet enchanting filmmaking. Ever the character, his intriguing bio bridges everything from monocles to S&M to fleeing Nazism to rumours of having murdered his first wife! More relevantly, he was a notoriously dictatorial presence on the film set; as such, many of his films—Metropolis and his equally noteworthy film noir M (1931), for example—deal with an individual being stifled by a collective authority (and this effectively traces another of his thematic tenets: a compassion for criminals). Despite his darker tendencies, however, Lang stands today alongside the likes of cinematic great Alfred Hitchcock (his contemporary in most every way, in fact) since both are similarly able to skillfully charm audiences with their engaging, subtly intricate films.

"Lang is a mix of artist and pulp storyteller, pessimist and entertainer. As much as any other film director he found how to fuse high and low culture in the new medium of the cinema." -Rob White, 2000, BFI

In the city of Metropolis, life is separated into two distinct groups: the cerebral managers who inhabit the city's towering network of skyscrapers; and the able-bodied workers who dwell underground performing robotic tasks in order to subsist their social/literal superiors. Ultimately, some form of 'heart' must be found to mediate between these 'heads' and 'hands.'

Set in a futuristic landscape so novel and inventive it practically prescribed what later sci-fi would look like, Lang's vision of this prospective world is as stunningly imaginative as it is visually compelling. (What's more, all of effects-expert Eugene Schüfftan's tricks—and there are many fascinating examples to behold—are done without anywhere near the equipment of modern visual effects artists—not even an optical printer!) The epic nature and sheer spectacle of Metropolis are still the film's most endearing features, but the restoration has nonetheless added various segments that aid in smoothing transitions, developing motivations, and expanding secondary characters.

"A masterpiece of art direction, the movie has influenced our vision of the future ever since." -Mick LaSalle, 2002, San Francisco Chronicle

"That Metropolis has been considered a classic without truly having been seen says much about the power of its images. Now fully revealed, it is all the more amazing." -Tom Long, 2010, Detroit News

Praise for the Alloy Orchestra is in no short supply; indeed, it's difficult to find a mention of their work that isn't teeming with superlatives and awe-struck affection. Technically, they are a three-man musical ensemble from Cambridge, Massachusetts; the sound of their pieces, however, is more often compared to that of a full-fledged orchestra:

An unusual combination of found percussion and state-of-the-art electronics gives the Orchestra the ability to create any sound imaginable. Utilizing their famous "rack of junk" and electronic synthesizers, the group generates beautiful music in a spectacular variety of styles. They can conjure up a French symphony or a simple German bar band of the 20's. The group can make the audience think it is being attacked by tigers, contacted by radio signals from Mars or swept up in the Russian Revolution. -Alloy Orchestra Website

There's only three of them, but with keyboard, accordion and clarinet, and an array of various percussion instruments they created a wonderful, clamorous score with pulsating tom-tom rhythms building the climax to a pitch of intensity that was almost physical. The cumulative effect surpassed expectations: a joyful, thrilling evening, and a truly triumphant restoration. -Tom von Logue Newth, 2010, ScreenCrave

"If more silent movies had received a live accompaniment from the Alloy Orchestra, those new-fangled talkies might never have taken off." -Bruce Stirling, The Dominion"

Akira Kurosawa's Ikiru (1952)

7:00pm, Monday, November 1, 2010

12:00pm, Saturday, November 6, 2010

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG | 143 mins | Japanese with English subtitles | B&W | 1.37:1 | 35mm

Kurosawa returned two years after Rashomon with his caring and poignant rendition of personal struggle to find meaning in life. The sad protagonist in Ikiru (1952) is "an aging widower, a petty government official who has done nothing but shuffle papers and pass the buck for thirty years." (Crowther, 1960) Struck with cancer, the man determines to redeem himself for his past inaction by wholeheartedly devoting himself to the completion of a single counter-bureaucratic endeavour: getting a children's playground built before he dies. Though Kurosawa's technical genius often shines through the heart-wrenching emotion, it only serves to deepen our empathy for his characters; his humanism is thus at its peak, and this film is essential viewing as a result.

"You see more human nature and more Japanese customs in this film—more emotion, personality and ways of living—than in most of the others that have gone before.Bosley Crowther, 1960, New York Times" "The film is a Samurai-free study of aging and contemporary values. … Kurosawa's tone is social realist, the closest "the emperor" ever came to being Vittorio De Sica.Michael Atkinson, 2002, Village Voice" "I think this is one of the few movies that might actually be able to inspire someone to lead their life a little differently. … Over the years I have seen Ikiru every five years or so, and each time it has moved me, and made me think. And the older I get, the less Watanabe seems like a pathetic old man, and the more he seems like every one of us." -Roger Ebert, 1996, Chicago Sun Times

In this film Kurosawa's humanism was at its height. This discursive film is long and varied; it winds and unwinds; it shifts from mood to mood, from present to past, from silence to a defeaning roar—and all in the most unabashed and absorbing fashion. Its greatest success may be in its revitalization of film technique." -The Japanese film: art and industry" by Joseph Anderson & Donald Richie, 1982

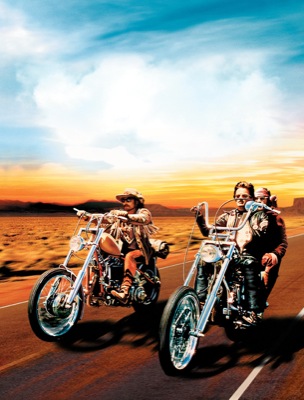

Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider (1969)

Newly restored 35mm print!

7:00pm, Thursday, October 21, 2010

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A | 95 mins | English,Spanish | B&W,Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

The Calgary Cinematheque is pleased to present a one-night-only showing of Dennis Hopper’s newly restored 1969 masterwork: Easy Rider.

Chronicling the meanderings of two motorcycle-borne Americans, the film’s plot offers up as much artful film style as it does genuine cultural, social and historical intrigue; the open road, the drug trips, the free love—Easy Rider doesn’t define a generation so much as it captures one in all its naturalistic, poignant honesty.

"[Billy and Wyatt] don't communicate with us, or each other, but after a while, it doesn't seem to matter. They simply exist … We accept them in their moving isolation, against the magnificent Southwestern landscapes of beige and green and pale blue." -Vincent Canby, 1969, NYT

After a big Mexican cocaine haul, Peter Fonda’s Wyatt (aka ‘Captain America’) and Dennis Hopper’s Billy (aka ‘Billy The Kid’) hit the road to do their own thing in their own time as they cruise towards New Orleans, Mardi Gras and Florida retirement. Along the way, they encounter a real live hippie commune, Jack Nicholson’s football-helmeted ACLU lawyer, some hippie-hating rednecks, a French Quarter working girl, and the screen’s baddest acid trip ever. Whether out of nostalgia or curiosity, to watch Easy Rider is to join Wyatt and Billy on their intangible quest for freedom; it’s a liberating journey, no doubt, but one whose final destination might just throw the very nature of freedom into question.

The film won a special prize for Best First Work at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival, and helped to unofficially launch the new wave of American “independent” filmmaking that has come to be known as the New-Hollywood era (which also includes the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Altman, Sidney Lumet, and Arthur Penn, among many more). Jack Nicholson’s breakout role as drunkard lawyer George Harrison was enough to earn him an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and, indeed, his character’s aura permeates many of the film’s most unforgettable moments. Easy Rider is not to be missed—whether you’re a ‘flower child’ yourself or just have parents who were!

"Does Easy Rider take its heroes to be prophets or fools? Does its apparently romantic view of antisocial roaming contain an element of satire? The movie itself plays its cards close to the fringed buckskin vest, grooving on the American landscape rather than spelling out its meanings. Mr. Hopper, a sly showman and a cunning formalist, blended the stripped-down muscularity of contemporary hot-rod B-movies with flights of abstraction and intuition that show more than a passing acquaintance with art-house heroes Michelangelo Antonioni and Jean-Luc Godard." -A. O. Scott, 2009, NYT

About the Restoration

Although initially restored in 1999 through a complicated mixture of photochemical techniques and old digital technologies, there were still many issues that couldn’t be fully addressed at the time. For this new restoration, Sony began with a 4K scan of the best surviving 35mm film elements; following an extensive digital restoration, with the repair of all torn frames and scratches and the removal of all dirt from the image, a brand new 35mm negative was created, from which new 35mm prints have been struck. -Film Forum

Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1950)

Newly restored 35mm print!

7:00pm, Tuesday, October 5, 2010

12:00pm, Saturday, October 9, 2010

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG | 88 mins | Japanese with English subtitles | B&W | 1.37:1 | 35mm

Repeat screening accompanied by Film School lecture: "Akira Kurosawa and Post-War Japanese Cinema" by Maurice Yacowar, Emiritus Professor at the University of Calgary.

"Rashomon was more than just commercial entertainment. It was a film of ideas, made by a serious artist with a sophisticated aesthetic design." -Stephen Prince, 2002, Criterion

Ushered in from another medium, Akira Kurosawa started off as a painter, and it shows most in his use of the telephoto lens that flattens on-screen space into more abstracted compositions. His keen eye for visual elegance, coupled with his strict attention to detail and dictatorial perfectionism (his nickname being "Emperor") allowed him to attain a level of mastery yet unmatched in Japan's history. Indeed, he is not just the best known Japanese director, he continues to be praised and idolized as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time by fellow cinematic notables—from Bergman and Fellini to Spielberg and Scorsese.

His fame began in 1950, when Rashomon's surprise victory at the Venice Film Festival propelled him—and Japanese film in general—into the international spotlight. The film's title literally denotes a location in the film, but has come to signify the 'subjectivity of perception on recollection' owing to the way in which Rashomon's four main characters each give mutually contradictory yet equally plausible accounts of the very same event.

Brimming with action while incisively examining the nature of truth, Rashomon is perhaps the finest film ever made about the philosophy of justice. Through an ingenious use of camera and flashbacks, Akira Kurosawa reveals the complexities of human nature as four people recount different versions of the same story: the murder of a man and the rape of his wife. Starring Toshiro Mifune in a commanding performance, Rashomon revolutionized film language and introduced Japanese cinema to the world.

About The Restoration

Rashomon was restored by the Academy Film Archive in association with the Kadokawa Culture Promotion Foundation and The Film Foundation. The project began with a survey of the world's film archives to discover what film elements still existed. The original camera negative and soundtrack—originating on highly flammable nitrate film stock—were known to have been destroyed when the storage of nitrate was prohibited in Japan in the 1970s.

The best surviving picture element was a 35mm release print, made from the original nitrate negative, held within the collection of the National Film Center (NFC) in Tokyo. The print was scanned at 4K resolution, and digital tools were used to clear the scratches, dirt, stains and other defects that existed in virtually every frame. The numerous pops, hisses, crackles and distortions on the print's audio track were also digitally removed.

Image Restoration

Several missing frames from the NFC print were found in alternate elements in Fine Grain Master Positive in the Kadokawa Foundation's library. Nearly every shot contained a scratch, a dig, a scuff, a piece of dirt, an abrasion, stain, or artifact of some kind. As the majority of these age-induced artifacts were part of the print image, the only way to address them was through digital technology.

The images were processed at 2K resolution by Lowry Digital. Many of the procedures required hours of frame-by-frame correction by a team of digital artists using image processing and visual effects software.

After all of the artifacts had been removed and the picture completely restored, Rashomon was output back to film at 4K resolution onto two new polyester digital intermediate negatives—one which will reside in Japan and the other at the Academy Film Archive in the U.S.

Audio Restoration

Both the 1962 NFC print and the Fine Grain Master Positive were transferred into the digital realm at DJ Audio in Studio City, California. A large number of pops, hisses, crackles, and other audio distortions had been introduced into the track over the years while some anomalies may have been present at the time of the film's original release. At Audio Mechanics in Burbank, the defects were digitally removed and the audio continuity restored.

New elements were created of both the raw and restored files on digital tapes and drives as well as on new film and magnetic track elements. Sets of both elements will be stored in Japan and at the Academy Film Archive in the U.S. -Janus Films

Apichatpong Weerasethakul's Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010)

2010 Cannes Palme D'Or Winner!

7:15pm, Friday, October 1, 2010

Calgary Cinematheque sponsored event

Eau Claire Cinemas 200 Barclay Parade SW

PG - Frightening Scenes | 114 mins | Thai with English subtitles | Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

Co-presented with the 2010 Calgary International Film Festival.

Visit the CIFF website for more info or to buy tickets.

Boonmee, a widowed land owner, struggles with failing kidneys and loneliness. Retreating to his farm with his closest family and supporters, Boonmee prepares for his final phase and together the family recollects lazy memories. Strangely, forest ghosts and creatures transformed from Boonmee’s past begin to gather at the home for a nighttime mix of inexplicable myths and animalistic fable.

This year’s Palm D’Ors winner at Cannes has already been touted as the most experimental and critically deserving film to screen on the French Riviera in some time. Having transitioned from hisses at Cannes in 2004 to standing ovations in 2010, the world finally seems ready to appreciate the distinct and subtle cinema of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives is proof that this filmmaker is a one-of-a-kind master, and those willing to succumb to this film will be forever intrigued by the ease with which it bleeds between beautiful naturalism and puzzling fantasy. -CIFF

[Apichatpong] is also a polarizing figure in Thailand, although not as much for his films, which until recently were barely known among the general public, as for his championing of anti-government protesters and his biting critique of the political establishment.

But Uncle Boonmee does not come across as a political film. Still, Mr. Apichatpong's empathy for northeastern Thais, who have traditionally been manual laborers and farmers, shines through. The film's characters disparage big-city life and speak a dialect close to the Lao language, which is not spoken by people born and raised in Bangkok. To the outside world Uncle Boonmee is a Thai film, but viewers in Bangkok relied on Thai subtitles to understand the northeastern vernacular. -Thomas Fuller, 2010, NYT

Like most of his feature films, Thai auteur Apichatpong Weerasethakul's Uncle Boonmee is set in Isan province, where he grew up. It playfully invokes both the lifestyle and animistic beliefs of the Northeast country folk, and the primitive magic of early Thai cinema, relating both of these to his musings on reincarnation … This view of reincarnation as all beings coexisting in one non-linear universal consciousness is also central to Apitchatpong's conception of cinema as the medium with the power to replay past lives and connect the human world to animal or spiritual ones. That may be why he shot the last scenes involving parallel worlds in 16mm, as homage to the format of film in his childhood memory. His casting of actors or roles (like a monk, a Burmese worker) from previous films in also a kind of reincarnation of the director's cinematic past lives.

The director's film language has always been experimental, intuitive and personal to the point of mystical … The natural locations (especially the cave glittering in the dark) exude cosmic energy, while sound extracted from wildlife plays as significant a role as an animate being. -Maggie Lee, 2010, The Hollywood Reporter